Spain 14th Century

Varsano literally means one who is from Vars in medieval Spanish. I was unable to determine precisely when my family immigrated to Spain, but I may assume it was sometime after King Phillip retracted Jewish expulsion in 1180 but before 1394 when all Jews were expelled from the kingdom of France. When they arrived in Spain, they were absorbed into a flourishing Jewish community that had existed since the 4th Century. Since Vars commune was in the South of France on the Mediterranean, my family probably made a relatively short journey around the Gulf of Lions to Northeast Spain. They most likely settled in a city with a sizable Jewish population with a similar climate and feel to Toulon or Marseilles along the Mediterranean Sea. Barcelona of Valencia Catalonia was the closest such city that offered safe harbor. History Professor Llorenc Mercadal Fernandez adds that the Varsano Family went to Barcelona, Gerona in Catalonia, and la villa de Caceres. The existence of the “la sinagoga de los franceses,” or French Synagogue, in the Jewish Quarter of Barcelona further confirms the claim.

According to Ancestry.com DNA test results, my ethnicity estimate for Spain is 2%, but it can range from 0 to 11%. Given that there is written evidence of various members of the Varsano family living in Spain during the 15th Century and the family name being Spanish, I found the ethnicity percentage to be rather low. However, my understanding of the DNA testing technology is that it traces back for approximately 500 years. My DNA test results are from 2022, so 500 years prior would be 1522, which is at least 30 years after leaving Spain. It seems like a logical explanation for the low percentage in Spain and may also be a reason why France or Provence do not register on the DNA test results. Regardless of the precise percentage, the test results are further evidence of a Varsano presence in Spain during this period of history. What was life like for the Varsano Family and their peers in the Jewish community of Spain?

Jewish communities experienced a “Golden Age of Sephardim” during the Moorish, or Moslem, rule of Spain. Jews were tax officials, doctors, merchants, and craftsmen. Most of the Jews of Spain lived in the so called royal cities of Cordova, Granada, and Toledo. However, Barcelona and other urban concentrations had significant scientific, artistic, and intellectual circles of Jews. Cordova was the capital of Moslem Spain. Located next to the main mosque was the Juderia, or Jewish quarter. Although it is difficult to determine, exactly where and when the Varsano family arrived in Spain, it is known that Ladino was spoken by many generations of my family. My father, Mordecai Varsano, spoke Ladino which he was able to adapt to modern Mexican Spanish to converse with the Latino community in Southern California where I grew up.

The form of Ladino spoken while the Jews lived in Spain was essentially Medieval Castilian Spanish with some influences of Portuguese, Catalan, and Aragonese. As the Sephardim migrated to other countries, words from the languages of those countries were incorporated into the ever evolving language. Ladino, until recent years, was written in Hebrew rather than Roman characters which made it difficult for non-Jews to read. However, folk songs and prayers were chanted in Ladino which most Spaniards could understand. “Boca dulce abre puertos de hierro,” or “Kind Words open iron gates,” was a popular saying through the years and was a philosophy that helped the Sephardim live harmoniously with their Spanish neighbors.

The rich culture and adaptive nature of the Sephardim allowed them to prosper in Medieval Spain. A unique Sephardic Cuisine was developed starting around the 12th Century which incorporated Arabic influences of Moslem Spain into the Kosher Laws of Judaism. Sephardic food used the grains, nuts, seeds, vegetables, fruits, and meats of the Mediterranean region. Sephardic chefs, as well as Spanish chefs, historically loved rice because it was the favored grain of the regions of Andalusia and Valencia. In the Sephardic culture, rituals and traditions were often stronger than the religious beliefs. Judaism celebrates many holidays, and the Sephardim developed a different menu to correspond to each holiday. The dishes were named according to biblical stories that integrated the eating experience with Jewish study to create a “Holy Cuisine.” Food became both ceremonial and celebratory. Following the traditional prayers, it was not unusual for a family dinner to burst out into Ladino folk songs and dances.

All aspects of Jewish life flourished like they never had before. From cuisine to theology, from painting to poetry, from politics to business; Judaism in Spain blossomed. In the 10th Century, the Christians began the crusade of conquering of Spain known as the Reconquista. During the Reconquista, many Jews came under Christian rule and were forced to adapt to a new set of regulations. The cultural progress of the Sephardim was interrupted by not yet halted by the Christian conquests. During the Reconquista, the Jews of Moslem Spain scattered throughout Moslem and Christian regions, and slowly regained some of their previous stature but longed for the golden days of Cordova rule.

Many Jews helped the Christians and consequently received rewards. In the 11th Century, the Christians conquered Toledo and granted leading Jews positions as diplomats, tax officials, scientists, and medical occupations. Many of these positions depended on the king’s appointments, so favoritism rather than skill was the key to advancement. To the Christian Church, Jews were to be kept separate and urged to convert. Jews were never allowed to be at the top levels of government. Following the Christian conquering of Moslem regions in Spain in the mid 13th Century, the Jewish learning centers of Granada and Cordova were destroyed, but a rich cultural life for a large number of Jews persisted in Barcelona and Toledo.

In 1263, at the Cathedral of Barcelona there was a debate between Judaism and Christianity. Nachmadidis represented the Jews and Pablo Christiani represented the Christians. After four days, the debate was halted and Nachmadidis was exiled for the blasphemy of arguing in a more compelling manner than the Christians. As a result, Jewish books were subsequently censored and other restrictions were imposed. Conditions for Jews would continually deteriorate over the next few years. In the 14th Century, the Bubonic Plague, or Black Death, took the lives of droves of people throughout Europe. The ignorant beleaguered masses took revenge on the convenient scapegoat of the Jews. Out of revenge, many innocent Jewish families were slaughtered because of a terrible disease epidemic.

In addition to blaming the Jews for the Bubonic Plague, the Catholic Church was stepping up its efforts to convert Jews to Christianity. In the year 1391, the 700,000 Jews that lived in Spain were cut into thirds. 1/3 were killed or exiled. 1/3 converted to Christianity and 1/3 survived as Jews. The Jews of Barcelona were also forced to convert to Catholicism.

15th Century Spanish Inquisition and Exile

In 1412, the preacher monk named Vincent Ferry strongly urged Jewish conversion. Reformatory Laws were imposed that stated Jews and Christians must live separately. Jews must also wear a badge. Christians could not be treated by Jewish doctors. Jews could not do business with Christians. The Jews communal autonomy was taken away. Many Jews felt that they had no choice but to convert. Because of many logistical problems, some of the laws were eventually revoked or softened, the smaller Jewish population persisted.

In August of 1412, Haranimo de Santa Fe, a former Jew, became the doctor to the Pope and issued a memorandum on the Jewish “problem.” In January of 1413, the Pope orders Jewish representatives of Aragon to the Papal Court to answer the questions of Haranimo’s Memorandum. The blatantly biased disputation was conducted by Haranimo himself in “debate” sessions. He tried to convince the Jews that Jesus was the messiah for 18 months and at its conclusion was considered a victory by the church. Unfortunately for the church, the Pope abdicated and the Jews got a temporary reprieve.

Jewish communities were at the mercy of the ruling Catholic monarchs. Jews in cities were forced to convert because they had no power otherwise. In the countryside, there was a strong Jewish tradition and Conversos practiced “secret” Judaism. Conversos were accepted by Jews. They were circumcised and received a Jewish burial.

To the Christians, the Conversos were considered Christians. Many achieved high levels of power. However, they were resented by many because it was believed that on the outside they were Christians but on the inside they were Jewish.

In 1469, Isabella wed Ferdinand in her hometown of Segovia. Both Jews and Christians were welcome at the national wedding and celebration. By 1474, Ferdinand and Isabella were jointly reigning over Castillo. In 1479, Ferdinand ascended to the thrown of Aragon and the two major kingdoms of Spain united. The main goals of the new rulers were to conquer Granada, the last stronghold of Moslem Spain, and start an inquisition to solve the Jewish problem thus fully integrating all Conversos.

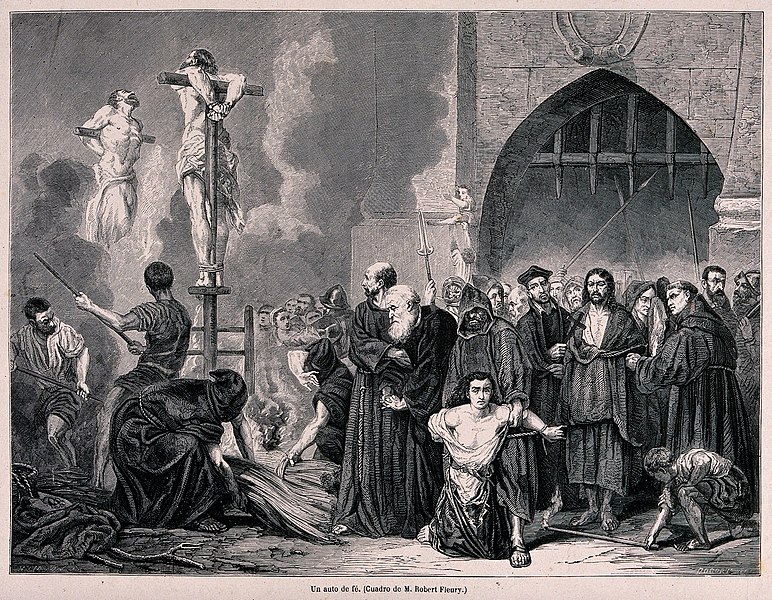

The Spanish Inquisition was an ecclesiastical tribunal established by the Pope at the request of the Catholic Kings to combat former Jews, Muslims, and Illuminists, as well as those accused of witchcraft or sorcery. In 1478, the authorization to name inquisitors was given and by 1483 the Grand Inquisitor of Domican Tomas de Torquemada was named. The Spanish Inquisition officially began in 1484 in the city of Toledo. However, forced conversions and unfounded killing of Jews began centuries earlier. The inquisition was merely a horrific escalation of these injustices. The inquisition sought to exile Jewish heretics and save the souls of lapsed Conversos by burning their bodies at the stake. Information and testimony was obtained by the use of torture and confiscation. Approximately 2000 people were burned at the stake through elaborate ceremonies during the public sentencing in the town center. According to Professor Fernandez, Victoria Lopez Varsano (or Barsano) was burned at the stake for observing Shabbat and her sister was put in “perpetual prison.” Also, Rogelio Varsano was punished for prayer in “jude mode.”

In “” by Haim Beinart writes about the Jewish Life of Conversos. Mr. Beinart states “It has already been noted that Jews who visited Ciudad Real slaughtered to supply the Conversos’ needs. For a period of 20 years starting from 1444, there was a Jew who slaughtered in Juan Falcon’s yard every time he reached the town, similarly there was a Jew who slaughtered in Rodrigo Varsano’s back yard in 1464 or 1465. Fernando de Trujillo, when still a Jew, slaughtered for Conversos of Ciudad Real who fled Palma, this at the time he was serving as their rabbi; and at the home of the tax farmer Juan de Fez the Jew Maestre Angel, resident of Guadalajara, slaughtered in 1459/1460. Rodrigo Varsano was one of 21 Jews in Ciudad Real in which his yard ritual slaughter was carried out. Rodrigo Varsano was a Jew who slaughtered in his house revealed during the trial of Juan Gonzales Escogido according to testimony by Francisco Hernandez de Torrijos.”

Why was the slaughtering of meat so important to the Jewish community and how did they hide from the inquisitors? Mr. Beinart explains “The slaughtering of meat according to the ritual laws of kashrut, and all that the eating of kosher meat entailed, is another aspect of the Jewish life of the Conversos of Ciudad Real that deserves to be highlighted. A study of the measures they took to ensure a supply of ritually slaughtered meat indicates how great a place this issue occupied in their lives. It was not easy for them to refrain from purchasing meat at the town abattoir, the more so since in all localities they were obliged to pay the tax levied on meat. In those days there was no such thing as a butcher who kept slaughtered meat until a customer came to buy it; on the contrary, animals were slaughtered when there were customers to purchase the meat. Hence when Conversos wished to buy kosher meat they undoubtedly had to agree among themselves beforehand on the slaughter of a beast. Furthermore, they did not eat meat every day; there were a whole series of days on which the Church forbade its consumption, so the Conversos had to be doubly careful neither to slaughter nor to cook and eat meat dishes on these occasions.” Despite these persecutions, at least some members of the Varsano family persisted into the late 15th Century in Spain. However, forces behind their control would eventually cause them to find a new home yet again.

In 1491, the Moslems at Granada surrendered to the Christians. On January 6, 1492, there was a Royal Procession in Granada to commemorate the uniting of Castille and Aragon. With the Moslems defeated, a united Catholic Spain sought to vanquish any trace of Judaism from its country. On March 31, 1492, the edict of expulsion for the Jews of the Spanish Kingdom was signed by Ferdinand and Isabella. Unbelievably, the Spanish edict of expulsion remained officially in force until 1968 when it was rescinded by the Spanish government.

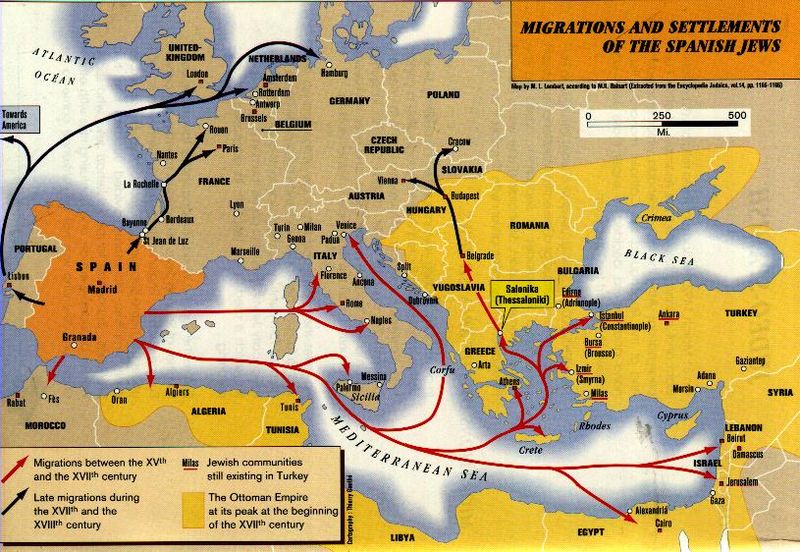

On May 1, all the Jews of Spain were given three months to leave every region within the Catholic Kingdom. They were not allowed to take any gold, money, livestock, guns, or anything of tangible value. The only items they were allowed to take with them were the essentials of food and clothes. King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella managed to expel approximately 150,000 Jews within four months of their edict. The Jews expelled represented ten percent of the total Spanish population. The whole of Western Europe was closed to Jews except for a few towns in Italy. Thousands of other Jews converted to Christianity to avoid facing the unknown. The Port of Cadiz on the southern coast of the province of Andalusia was the departure point of many. Seville and Tortosa were other departure points. Contracts with Basque, Portuguese, and Genoese ship owners were made to sail Jews to Italy and North Africa.

Most Jews, however, were not fortunate enough to leave by ship and simply walked away from the country that had been their home for hundreds of years. 120,000 Jews went on foot to neighboring Portugal who would exile them again only a few years later. 50,000 crossed the straits of North Africa. The Ottoman Empire welcomed the Jews, and many exiles went directly to the Moslem ruled lands to the east. Others chose a different route.

The Port of Palos was the departure point for the ships carrying thousands of exiled Jews as well as the Nina, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria of Christopher Columbus’ famous voyage. Columbus’ voyage was partly financed by confiscated Jewish property according to the 1492 expulsion edict. In fact, Columbus’ historic journey was delayed several days because of the mass exile of the Jews. On October 11, 1492, the last Jews left Spain, followed by Columbus on October 12. Continue to the Kingdom of Naples