Bulgaria 1878 Independence to 1948 Departure

Bulgarian Independence

When Bulgaria gained autonomy in 1878, the Jewish community retained a special status with substantial self-administration under a chief rabbi. In a census of 1881 (which omitted Eastern Rumelia), 14,000 Jews are listed. The 1893 census shows some 28,000 Spanish-speaking (Sephardic) Jews out of 3.5 million people. The number of Jews rose at the same rate as the overall population, remaining just under 1 percent. In 1910, there were 40,000 Jews, out of a population of 4.4 million. Most lived in cities, especially Sofia.

After Bulgaria received its independence from the Ottoman Empire, it was forced to cope with the problems of modernizing an underdeveloped nation. The result was a nation with untested economic systems and precarious alliances. The ensuing fascist experiment would ultimately have a terrifying effect on Jewish families, including the Varsano families.

Following the establishment of an independent Bulgaria, the West became leery of a unified pro-Russian Bulgaria and sought to divide the country into segments. Bulgaria proper was now a separate region from Eastern Rumelia, Thrace, and Macedonia. The Bulgarian authorities felt they had the historic rights to these lands but begrudgingly agreed to the new constrictive borders. The Bulgarian leadership continually thirsted for the concept of a “greater Bulgaria,” which became a key factor in their alliances with Germany eventually resulting in the cooperation in the persecution of the Jewish population, including the Varsano family, in all Bulgarian held territories.

The national language of Bulgarian and medieval language of Ladino were taught to children while very few Jews even bothered to learn Hebrew. Similar to the late 20th Century in United States, the late 19th Century in Bulgaria saw many synagogues empty except for weddings, births, funerals, and the High Holy Days. For the Bulgarian Varsano families, contributing to the new independent country of Bulgaria became a higher priority than going to synagogue on a daily basis.

Balkan Wars and World War I

In 1912, the Bulgarians would instigate the Balkan Wars in order to recapture the “disputed” lands. The First Balkan War involved the Balkan League of Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, and Montenegro successfully dividing what remained of the Ottoman Empire. The Second Balkan War of 1913 resulted in Bulgaria being defeated by Serbia, Greece, and Romania primarily over the control of Macedonia and Thrace. Approximately 5,000 Jewish citizens of Bulgaria proudly served in the country’s military for these wars and suffered many causalities. The Jews of Bulgaria were mostly patriotic and the Bulgarian government appreciated their contributions until fascism took hold.

The Bulgarian leader prior to WWI was Tsar Ferdinand Radoslavov who professed an official policy of “strict and loyal neutrality” in the burgeoning war, but economic dependence on foreign nations and internal political pressures forced them to take sides. In 1914, the Bulgaria government accepted a loan of 500 million gold lev from Germany, while rejecting a similar offer from France because the French wanted the Bulgarians to pledge their loyalty to the Western powers in exchange.

Germany fully expected Bulgaria to join their war coalition as compensation for the loan. German companies also began to receive railroad construction contracts and mining rights within Bulgaria which would later be worked on by Jewish slave labor, which included Isaac Varsano during WWII.

The Central Powers of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire wanted Bulgaria to join their coalition because Constantinople and the Straits could be controlled, and Serbia could be attacked through Bulgaria. Bulgaria officially changed their ambiguous foreign policy to “armed neutrality” which was shortly followed by joining the Central Powers. By the fall of 1915, the Central Powers appeared poised for victory and the Germans offered Bulgaria the territorial gains of Macedonia and most of Thrace as a reward.

There were over 7,000 Jewish soldiers killed in action in WWI. Twenty-eight Jewish soldiers reached the distinction of being officers and three Jewish men even achieved the high rank of colonel.

Bulgaria Jewish Casualties in the Balkan Wars and WWI

Jaco Mordehay Varsano from Sofia died in combat in 1916

Leon Heskiya Varsano from Sofia died in combat in 1916

Benjamin Isaac Varsanov, from Sofia died in combat in 1913

Chelebi Varsanov from Sofia, died in combat in 1918

Joseph Moshe Varsanov from Sofia, died in combat in 1916

Nessim Varsanov from Sofia, died in combat in 1916

Samuel C. Varsanov from Sofia, died in combat in 1916

Bulgarian Officers

Samuil Chaimov Varsanov December 29, 885, rank of 2nd Lieutenant, possibly killed in combat in 1916 (see above)

Baruh Isaac Varsanov born in 1896, rank of 2nd Lieutenant

Joseph Isaac Varsanov born in 1896, rank of Lieutenant

Note: Varsanov was a Bulgarianization of Varsano. It was common in Slavic countries to add a “v” to make it sound more native. Middle names were not common, so the middle name on this list is the father’s first name.

As the devastation of war grew, the Bulgarian enthusiasm shifted to despair. The military began appropriating supplies from the civilian population to serve the troops. Inflation started to take its toll and a pre-existing black market exploded with ensuing corruption that lasted several generations. The financial reliance on the Central Powers tightened while public dissatisfaction and war causalities continued to rise. French and British troops led an invasion into war torn Bulgaria and by September of 1919, Bulgaria was forced to sign the Armistice of Salonika which gave back all of the “new territories.” A few days later, Ferdinand resigned in disgrace and abdicated his throne to his young son, Boris III. Followed shortly by the signing of the Treaty of Neuilly between Bulgaria and the victorious Allied Powers in which Bulgaria was forced to cede land to Greece and Yugoslavia, thus depriving it of an outlet to the Aegean Sea.

Most of the treaties that ended WWI sought to punish rather than rebuild the defeated nations which resulted in more radical forms of government. The downtrodden states of the former Central Powers were fertile grounds for fascism to take root. The years immediately following the war in Bulgaria were marked by servicing war debt, uneasiness with their Balkan neighbors, slow economic growth, temporary political coalitions, and a rise of socialism. The disgruntled Bulgarian people replaced the existing government with a new ruling party whose main goal was to consolidate power in order to promote economic growth which followed the model of the Italian Fascists.

Between WWI and WWII

Thankfully for the Varsano families of Bulgaria, the early form of a fascist government in Bulgaria was short-lived. While authoritarian governments and extreme antisemitism in the rest of Europe metastasized, the low profile Balkan nation of Bulgaria remained fairly insulated until WWII began. The Jews of Bulgaria were allowed the freedom to educate themselves as they saw fit and practice their religion without legal restrictions.

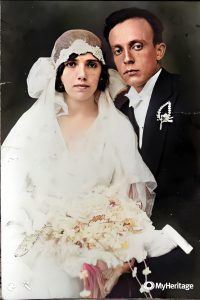

Most of the Bulgarian Jewish children of early 20th Century were educated in part by a French school known as Alliance Israelite Universelle (AIU). Although it taught Jewish studies, it was more of a secular education that spread the French culture. Sabetai and Isaac Varsano could fluently speak Bulgarian, French, and Ladino while many Jewish adults also spoke Greek and Turkish for business purposes. Although it had been centuries since anyone in the Varsano family lived in France, the French traditions had been reintroduced to the Jews from Vars. Bits and pieces of the French culture and language were eventually passed down to younger generation, but to a far lesser extent than the Sephardic culture of Spain.

The French cultural imperialism died out after several years and was replaced by Jewish Nationalism with an emphasis on learning Hebrew. In the early 20th Century, Zionist youth organizations captured the spirit and political diversity of the Jewish families of Bulgaria. In addition to educating the children, these groups were also a social outlet and a center of activity best illustrated by the sports oriented group Maccabi. The Maccabi club was modeled after the Yunak Bulgarian Athletic Youth group and the Sokol organizations of other Slavic countries. As a child, Isaac Varsano of Sofia wore the Maccabi uniform which was the colors of the Zionist flag splashed with Bulgarian pride; white shirt, blue pants, a Bulgarian flag ribbon, and finished off by a blue and white hat. An intermingling of loyalties was a common practice among the Jews of Bulgaria.

Isaac Varsano’s generation was loyal to their country, but wanted democratic change. They sought Jewish schools that were independent from the local synagogues. They strove for equal voting rights and representation regardless of position or wealth. They wanted to change their own Jewish community at home while seeking to establish a Zionist infrastructure with other Jews around the world. The urge for a creating a better life was instilled in my father at a very early age. His parents taught him the importance of his heritage and the need to secure a homeland for the Jewish people.

The Bulgarian government before WWII was very tolerant of Zionist activity compared to other European nations. This phenomenon can be explained by the historical tolerance of the Bulgarian nation and the lack of political disturbances by Jews. Few Jews in Bulgaria were involved in national politics compared to other European nations. The main political cause of most Jews was Zionism, but they still remained loyal and patriotic citizens of Bulgaria. Eventually, assimilation and Zionism helped erode the traditional Sephardic culture and religious observances.

Jews experienced very little anti-Semitism in Bulgaria due to the multi-ethnic tradition of the country. The Turks and the Greeks were traditional enemies and a larger minority group than the Jews, so they received the brunt of Bulgarian xenophobia. Most Bulgarian politicians did not promote antisemitism and the average Bulgarian did not even come in contact with the mostly insulated Jewish community. Jews did not have high positions in the Bulgarian government and did not exercise significant economic influence over the country as their counterparts did in other Western European countries. Therefore, they did not experience economically based anti-Semitism like other Jews in Europe.

However, there were scattered antisemitic incidents within Bulgarian cities targeting Jewish populations mostly instigated by racist organizations from Vienna, St. Petersburg, and Berlin. The multiethnic Bulgarian populace was not a receptive audience to these forces and the intelligentsia publicly celebrated their policies on Jews and their tolerance of other cultures. Despite the nation’s resistance, the state sponsored antisemitism of foreign nations would continue to infiltrate and expand in Bulgaria throughout my father’s childhood.

While systematic anti-Semitism wasn’t prevalent, Mordecai “Seeco” Varsano of Sofia did experience isolated incidents of bigotry and discrimination. Christian boys would make derogatory comments about “Seeco the Jew,” and he would respond by getting the kid in a headlock with his left arm then punching him in the face with his right fist. He also said that throwing rocks was a good tactic against a larger opponent. Sometimes he unable to fight back against a more imposing force like when he was on the receiving end of some beatings from schoolmasters. Even though he attended secular schools, he was still a Jewish minority student in a predominately Christian school. While the teachers did not express overt antisemitism, some clearly had their prejudices. Corporal punishment was an accepted form of discipline and Seeco received spankings and was hit with a ruler for bad behavior. The more the teacher disliked Jews, the more severe the punishment was.

Meanwhile on the national scale, the Bulgarian leaders were governing their people in a similar manner to parents disciplining their children: authoritatively. The experimental fascist regime was short lived. It was eventually forced from power by military factions that took over the government and imposed dictatorial measures. They abolished all political parties and changed the representation of the Subranie (Bulgarian Parliament). Instead of political parties, Subranie members would represent classes of people such as peasants, workers, artisans, merchants, intelligentsia, bureaucrats, and professionals. Since Isaac Varsano owned a hardware store, so his family was designated a merchant class.

Meanwhile in nearby Germany, the popularity of the Nazi party spelled the end for millions of Jews on German lands, and would eventually directly affect the Jews of Bulgaria. In 1935, the Nuremberg Laws and the Law for the Protection of German Blood and Honor were instituted which denied German Jews rights of citizenship, as well as the right to marry German citizens. While Germany blamed it problems on minorities, Bulgaria tried to establish a system that would be fair to all of its citizens.

In the midst of Mordecai Varsano’s otherwise pleasant childhood, the economic crisis had led to an alliance between the workers and the peasants against bourgeois domination and fascism. The resented bourgeoisie consisted of former political party activists and leaders from the professions such as lawyers, financiers, industrialists, merchants and statesmen. Even though some merchants were considered bourgeois, Isaac Varsano was a Jew with no political ambitions and could not have been blamed by any reasonable person for the economic problems of the peasant and worker classes. The rise of communism and the strike movement helped to bring a demise to the government. The Bulgarian public was alarmed by the authoritarianism of the existing ruling party, so a coalition of various political factions effectively removed them from power. Consequently, a royal dictatorship headed by Tsar Boris III was declared—who would be the ruler had the power of life or death over the Bulgarian Varsano families.

The royal dictatorship was not an absolute monarchy, but a government of compromise. The three major political factions were the ruling party, the “legal” opposition of old bourgeoisie party men, and the illegal opposition consisting of Agrarians, Communists, and political exiles. The Fascists were a much smaller faction which did not attain the same level of popularity as they did in Germany and Italy.

Boris was relatively popular and created an economically stable country. He allowed an election in 1938, but the policy of no political parties was kept in place. The new government forced diversification which led to the dwindling of large state sponsored industries and started the growth of small private industries. Since Isaac Varsano owned a modest hardware store, the current economic trend was favorable for his business.

However, by the late 1930s, times were not good for all Bulgarians. Bulgarian commerce was still largely state controlled and centralized in Sofia despite diversification efforts. The social and political gap between the peasants in the rural regions and the modern urbanites grew wider. Most Bulgarian Jews, as well as the Varsano family, enjoyed the fruits of modern Europe in the late 1930s because they resided mostly in the prosperous cities and didn’t share the discontentment with the rest of the country.

By 1938, a second set of Nuremberg Laws in Germany was set forth that further persecuted and humiliated the Jewish population. Jews were forced to wear a Star of David and to live in ghettos. They were not allowed to ride public transportation or possess an automobile. Less than a year later, the Third Reich’s policies of rounding up Jews in an orderly manner began expanding to the new lands that they dominated and eventually to allied nations like Bulgaria.

Notwithstanding the royal monarchy, Bulgaria was collaborating with the other fascist regimes in Europe. Bulgaria had a social dependence on Italy because Boris was married to the daughter of King Victor Emanuel III of Italy. Bulgaria also had an economic and military reliance on Germany since WWI. Germany purchased two thirds of Bulgarian agricultural exports and provided Bulgaria with loans, industrial trade, and armaments. Many middle class Bulgarians were educated in Berlin, Munich, and Vienna. From the German strategic perspective, the Balkan nations were not an immediate military priority but economic domination was essential.

In early 1939 following Germany annexation of Czechoslovakia, Boris began to realize that an alliance with the Third Reich was the only way to avoid forced occupation even though he was more philosophically attuned to the Western powers. Tsar Boris and Adolph Hitler began to secretly negotiate the terms of their pact. Bulgaria wanted the land lost in the Treaty of Neuilly, including Dobrudja from Romania and Thrace from Greece. The Germans agreed to let the Bulgarians acquire these “new territories” in exchange for mining rights within rural Bulgaria and other forms of non-official cooperation.

Throughout the early years of the war, Bulgaria positioned itself with the anti-Western forces which also turned out to be extremely anti-Semitic forces as well. Following the formation of the Nazi-Soviet Alliance, the Bulgarian-Soviet Commercial Treaty was signed and the pro-Western Prime Minister, Georgi Kioseivanov, was deposed in favor of the pro-German Bogdan Filov.

Filov’s regime was pro-German and antisemitic from the outset which set the tone for Bulgaria’s participation in WWII. Bulgaria had indeed emerged from the shadows of Turkish rule to become a more modern and more militant nation. After being soundly defeated in the Balkan Wars and WWI, the still recovering nation turned to a more brutal and long term form of fascism for what they believed would be an expedient ascension to world prominence. The Bulgaria people were desperate to recover from failed military campaigns and prosper economically by any means possible.

The Jews and other minority groups of Bulgaria would suffer greatly under Filov’s government. The unfolding of events within Bulgaria following their independence in 1878 until WWII, points to clear alliances with the Germans and their susceptibility to a form of government that emphasized nationalism and authority centered around one leader known as fascism. However, Bulgaria’s alliances of convenience contradicted the region’s centuries-old policy of tolerance and would prove to be detrimental to the nation for many years to come.

During Filov’s reign of terror, Mordecai Varsano would have his dreams shattered and his innocence robbed. The Varsano families had been contently settled in Bulgaria for about 400 years. They were patriotic and law abiding citizens that directly contributed to the well being of the community by gainfully employing Jews and non-Jews alike. For the most part, no Varsano families were ever a radical or revolutionary, and they even passively accepted their role as discriminated minority group as long as they could earn a living and keep their traditions. They weren’t interesting in ruling Bulgaria and were satisfied being willing subjects in a multi-ethnic society. After so many years of good standing, the faltering of the political structure throughout Europe would turn the Varsano families and their Jewish neighbors into unwilling enemies of their own nations.

World War II and the Holocaust

In the latter half of the year 1939, Mordecai Varsano turned seven years old and Adolph Hitler began his campaign of hate and subjugation across Europe. WWII would transform young Mordecai’s life from that of a privileged son of an affluent Jewish family to an impoverished child, lucky to escape the war with his life. At the onset of fighting, Bulgaria was already controlled by the Fascist Party which made joining the Axis powers inevitable. The next four arduous years saw the Jewish citizens of Bulgaria used as bargaining chips with the Nazi regime, with an ultimate deal that was unpredictably better for the Jews of Bulgaria than majority of European Jewry.

The vast majority of the Jews of Bulgaria were not accustomed to severe anti-Semitism, so as the war began, they were not too concerned about religious persecution. Mordecai Varsano was transformed from a naïve boy to a child that was mature beyond his years and well aware of his enemies. He spent his precious formative years under a brutal regime that deprived him of an authentic childhood.

The fall of 1939 marked the beginning of official government-sponsored antisemitic legislation. Starting in September, 4,000 Jews from Central Europe were temporarily in Bulgaria on route to Palestine. Instead of allowing them safe passage, they were deported to uncertain and problematic destinations. The next month, Aleksandur Belev, a pro-Nazi and rabid anti-Semite became head of the Bulgarian Government’s Agency regarding Jewish matters. Belev’s appointment was a terrible blow to the Jewish citizens of Bulgaria, and his policies would certainly become more inhumane as the fascist machine became more powerful.

In July of 1940, Bulgaria adopted the “Law for the Defense of the Nation,” or ZZN (Bulgarian acronym), which was a Slavic version of the Nuremberg Laws. Although there was some debate in the Subranie over whether anti-Mason and other anti-union type legislation should be included in the law, the sections regarding restrictions on Jews passed rather easily. Filov instituted a Nazi-type youth league that would fundamentally divide all of the children of Bulgaria into the majority Christians against the other minority groups. The honeymoon of Mordecai Varsano’s youth was over by his eighth birthday. It was clear that Tsar Boris and the Bulgarian government felt that the Jews were expendable and were prepared to use them as a negotiating tool for international diplomacy.

Financially, the Bulgarian people had no problem exploiting their Jewish neighbors. Confiscation of Jewish property under the ZZN was aggressively enforced. Special taxes were imposed on Jewish families and businesses. In spite of the government’s new policies, the Varsano family of Sofia was still able to live a decent lifestyle, but the constrictive net of antisemitic legislation was slowly closing in on them and depriving them of the amenities and achievements that Isaac and Rachel Varsano had worked so hard to achieve.

The ZZN was humiliating for Jews, but all parts of the law were not stringently enforced at first. Article 33 stated that Jews that served in the Bulgarian military or converted to Christianity enjoyed special privileges and were exempt from restrictions in some cases. This loophole helped many families, including the Varsanos.

The leaders of the well organized Jewish community in Bulgaria began making attempts to transfer their people to a safer country with the most logical destination for those seeking refuge: Palestine. However, British, Bulgarian, Arab, and German officials made mass emigration to the Holy Land nearly impossible. The entire Jewish community of Europe tried to get a limited number of children to the safety of Palestine, but with only scattered success. The SS Salvator from Bulgaria, overcrowded with desperate Jewish passengers, barely reached its destination of Haifa, Palestine. The British port authorities sent the unstable ship back to sea and she eventually sank in the Turkish straits, killing 280 passengers and dealing a devastating blow to the hopes of the Zionists. Isaac, Rachel, Mordecai, and Sarah Varsano decided that they would ride out the war in Bulgaria, and hope for the best.

Meanwhile, authorities within Bulgaria had made a deal that would essentially trade land for Nazi cooperation. Bulgaria would comply with Germany political plans, and in return Germany coerced Romania to cede Bulgaria the region of Dobrudja with its 5,000 Jewish residents.

The Reich forcefully encouraged its neighbors to fully embrace their Nazi ideologies. Boris gladly accepted the spoils of fascist conquests and became a good friend of the Germans. He began renaming the streets of Sofia to identify the country’s new heroes. Adolph Hitler, Benito Mussolini, and Victor Emanuel III all became new street names in my father’s hometown. Practically overnight, the familiar avenues of his innocence vanished.

In October of 1940, Italy invaded Greece, but Bulgaria which was officially neutral declined any obvious involvement in the military action. The Bulgarians were still interested in re-acquiring Thrace and would be passive during the Italian operations. Greece would be a tragically brave example of a Balkan country that fought the tyrannical forces of fascism rather than embracing them.

Italy’s attempt to conquer Greece failed. The battle of the two empires of antiquity ended in a Roman defeat, but the modern day Nazi storm troopers accomplished what the Italian legions could not. In order for the German invasion – known as Operation Marita – to be effective, the Axis troops would have to go through Bulgaria. Lured by the promise of territorial gain, Boris allowed the Germans safe passage and support on their way to fighting the Greeks. As a reward for their complicity, Bulgaria would receive the region of Thrace which had about 6,000 Jewish residents.

Bulgarian support of Operation Marita effectively ended their tenuous neutrality, and in March of 1941 Bulgaria entered the Three Power Pact Alliance with the Axis countries. A few weeks later, Yugoslavia signed the Three Power Pact for similar reasons as Bulgaria. However, shortly after the Yugoslavian decision, an internal coup instituted an anti-Nazi government in the capital city of Belgrade. Berlin responded by including Yugoslavia in their invasion and conquest plans of Operation Marita. The Yugoslavian coup furthered Bulgaria’s alliance with Germany because of the prospect of even more territorial gains from their neighbor to the west. Bulgaria went a step further in December when it declared war on the United States and Great Britain, but stopped short of a war declaration on their Slavic brothers in the Soviet Union.

With the help of German advances in Yugoslavia, Bulgaria annexed Macedonia which it added to its war chest of “recently liberated territories.” The Macedonian region, along with their 8,000 Jewish residents, would be governed by Bulgaria rather than locally controlled. The fate of the Jews in the new territories would help delay the persecution of my father in coming years. Every asset of a nation, including its people, became negotiating tools to be exploited for strategic importance. The location of Bulgaria was a major asset and its leaders intended to use their geopolitical position for the maximum amount of gain.

Before the German invasion of Russia began, both sides courted Bulgaria for their political support. The Soviets, led by Joseph Stalin, were pressuring the Bulgarians to sign a mutual defense pact. Boris, clinging to the unrealistic notion of neutrality, refused Stalin’s request and thus angered many Bulgarian communists. Great Britain also wanted Bulgarian support in order to create a second front to the war in the Balkans for their strategic advantage. Germany, on the verge of committing tremendous resources to the Soviet offensive, did not want to exhaust troops and supplies to occupy the Balkan Peninsula. Germany needed to exert control of the Balkans while expending a minimal amount of capital and effort.

The German invasion of the Soviet Union had a severe impact on the Communist Party of Bulgaria (BKP). The party leaders, some of whom were Jewish, were rounded up and put into political concentration camps. In response, underground guerrilla militias consisting of an unusual coalition of communists, Greeks, Yugoslavians, and Jews began springing up throughout the country. Although there were only about 400 Jews in approximately 10,000 partisans, this represented twice their percentage of the total population. With the aid of the Western Allies and the USSR, the partisans became an overt nuisance and a significant internal political problem for the Bulgarian government.

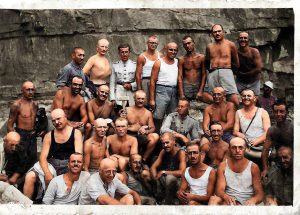

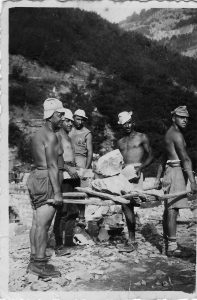

By September of 1941, the government closed the American College in Sofia, which had been allowing more than the mandated five percent maximum enrollment for Jewish students. Consequently Seeco (Mordecai Varsano) and Seli (Sarah Varsano) were forced to attend the remedial Bulgarian public schools. Previously, the ZZN required Jewish men of working age to serve in labor groups supervised by the Ministry of War, which was considered a somewhat patriotic duty because it contributed to the war effort. Under the new rules, Jewish men, including Isaac Varsano of Sofia, were put into forced labor crews under the Ministry of Public Works which was viewed as an obvious punishment that was not related to helping national aspirations. The slave laborers were also forced to shave their heads and many were treated in a degrading manner. On July 19, 1942 all Jewish men ages twenty to forty-five were to report for labor service on roads and railway beds in strategic parts of Bulgaria. Isaac Varsano was sentenced to work in a remote section of railroad near the Bof station. Isaac and his Jewish brethren were relatively lucky because he was not physically abused; he just had to work long grueling days for no pay.

Seeco and Seli were traumatized by the breakup of his nuclear family by the government authorities whose antisemitic net continued to close in on every Jew. Even though Isaac Varsano was in a forced labor camp, he could still visit his family occasionally. His appearance shocked my father because his freshly shaven head gave him an unusually depersonalized look—similar to concentration camp victims. A few years later, the Israeli military would not require their soldiers to have short hair cuts because of the Holocaust imagery of the bald headed captive. While Isaac Varsano spent hours of hard labor building railroads, my family heard rumors of other camps in Romania, Germany, and Poland where Jews were being exterminated. The labor camps in Bulgaria were viewed as a lesser evil, but there was a constant fear that they would be transformed into extermination camps.

In Germany, the brain trust of the Nazi Party reached a “Final Solution to the Jewish Problem.” Justifying that it was not possible to deport all the Jews to Palestine, Adolph Hitler and Hermann Goering—a leader in the Nazi Party and prime architect of the Nazi police—officially gave orders to kill all the European Jews. The Fuehrer and Schutzstaffel (SS) Commander Heinrich Himmler also made the decision to kill all the Jews in Russia during their planned invasion. The genocide of the Jewish people would be carried out in an orderly German manner which was outlined at the Wannsee Conference in January of 1942. Jews from various European countries were to be identified, rounded up, and deported to extermination camps in Poland with the cooperation of Nazi and local officials.

By the spring of 1942, Jews of Bulgarian citizenship living within the Reich and its protectorate (a masked form of annexation) were deported to the exterminations camps in Poland. Tsar Boris was again sacrificing Jewish rights at the behest of Hitler and was held up to other European leaders as a model of cooperation. In a meager attempt to appeal to humanitarian concerns, Boris temporarily refused to give up the Jews of Bulgaria citizenship that were living in France, Yugoslavia, and other occupied territories. Later, the Bulgarian authorities acquiesced to the Nazi plans, and stated that all Jews of Bulgarian citizenship living in conquered foreign countries were subject to German law.

The Varsano families of Bulgaria began to get the sense that no one was safe. Any citizen of country associated with the Reich, especially Jews, was merely at the mercy of their government’s whims and had little chance to voice opposition or exercise political rights. Isaac, Rachel, Seeco, and Seli heard that Jews across Europe were having their basic human rights unceremoniously stripped from them. Nothing was guaranteed because he had to rely on rumor and innuendo for news. The authoritarian regime controlled the media and truthful information was suppressed and manipulated for propaganda purposes. All that was certain was what was happening in your community that very instant. The future was fully dependent on how the battles in the war turned out and how the politician postured accordingly. They learned to trust only people close to him, namely Jews. Seeco and Seli also learned to rely on himself at an early age because their father might be taken away or murdered at any time. The basic traits of self reliance and distrust of outsiders stayed with Mordecai Varsano for the rest of his life.

The engulfing Bulgarian wave of Jewish maltreatment grew more powerful with the Decree of August 26, 1942. The decree strengthened the ZZN regulations and established a body within the Ministry of Internal Affairs called Komisarstvo za Evreiskite Vuprosi (KEV), or the Commissariat for Jewish Questions. The KEV would legally have the power to enact rules regarding Jews without the approval of the Subranie or the king. The familiar enemy of the Jews, Aleksandur Belev, would run the newly empowered government agency.

The KEV under Belev was a nightmare for the Jewish people, no matter how religious or politically active they were. A central point to the August 26 Decree was that a person’s ancestry rather than their religion was the key factor in determining who was a Jew. Unlike the Spanish Inquisition, conversion to Christianity could not dispel the hatred of the fascists. Article 29 stipulated that any unemployed Jews of working age would be expelled from Sofia. Consequently, Magazine Stomano (Isaac Varsano’s Hardware Store) became the employer of several Varsano family members and friends. Seeco and Seli curiously peeked through the keyhole of their parent’s room as they hid the French gold bullion coins in the hollowed out cores of the furniture from confiscation by the KEV treasury.

To combat this financial plundering, Isaac Varsano covertly made arrangements to funnel his savings to Swiss Bank accounts. These accounts were considered safe because Switzerland was neutral and the accounts were secretly number. Unfortunately, the Varsano deposits into Swiss accounts were never recovered despite the efforts of the legal community from the 1940s through the 1990s.

The KEV actively pursued the seizure of all Jewish assets. Cash, marketable securities, precious metals and stones were placed in separate accounts for “safekeeping” under the control of the commission. The bookkeeping for seized assets was corrupt and sloppy with the rampant misappropriation of Jewish funds to conspiring banks. KEV lackeys were even legally allowed to live in Jewish apartments. Objects of attributed value such as musical instruments and rugs were registered and placed at the disposal of KEV officers. Seeco’s beloved accordion and other furnishings of the Varsano family apartment were never to be seen again. The frivolous sounds of the wheezing accordion keyboard were replaced by the melancholy prayers for freedom that so many Jewish generations lamented.

The net of authoritarian confiscation had scooped up the cherished possessions of the entire family. The progressively intensifying persecution of the Jews of the mid 20th Century mirrored the censuring, restrictions, inquisition, and exile that our ancestors in Spain experienced 450 years earlier. No one ever imagined that history would repeat itself in such modern and apparently civilized times. The Varsano family realized that man was capable of committing atrocities no matter what era it was.

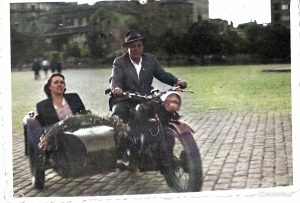

The commission sought to restrict Jews from participating in the formerly integrated Bulgarian society. By the end of 1942, Belev ordered the confiscation of all Jewish owned automobiles, motorcycles, bicycles, radios, and home telephones. Isaac Varsano’s convertible Fiat automobile and motorcycle with side car which gave him a great sense of personal pride were unceremoniously repossessed from him. Like the pre-Civil Rights Movement discrimination against “colored people” in the United States, Jews in Bulgaria were also restricted from visiting certain hotels, parks, theaters, and other public places.

In order to further their plans, an essential step for the KEV was to determine the designation and location of all Jews within the country. The ultimate goal of this information gathering process was to arrange for deportation with the SS. Stars of David marked all Jewish homes, businesses, and people. When the rule requiring the wearing of yellow stars was first established, there was a shortage of government issued stars. Some Jews decided to make their own custom stars to wear, complete with a picture of the King and Queen of Bulgaria. Even though the stars were meant to alienate and ridicule the Jews, many of them still felt patriotic towards the country that treated them as enemies

In spite of the Germans aggressively pressing for deportations, the Bulgarian government was somewhat apprehensive to deport all the Jews for several reasons. Legally, the Subranie was concerned with the precedent of deporting law abiding citizens of their country. Economically, they claimed the Jews were needed for road building and railway beds. Socially, deportations might cause unrest and political upheaval among the civilian population.

In the winter of 1942 Walter Schellenberg, head of espionage services (RSHA) for the Third Reich sent Berlin a secret report regarding the treatment of the Jews. The very critical and demanding report stated that Bulgarians were disinterested in deporting and persecuting Jews. It also said that the King’s royal court had Jewish connections that were reassuring their people that the worst was behind them. Although some of the report was accurate, much of it was hyperbole meant to incite anti-Semitic forces into action. Following the Schellenberg report, Theodor Dannecker was sent to Bulgaria by the foreign office and RSHA to accelerate the Final Solution in Bulgaria. Dannecker — who was previously the problem solver in charge of Jewish affairs in Paris — was an SS officer under the command of Nazi extermination expert Adolph Eichmann. In February of 1943, Belev and Dannecker sent a plan to Gabrovski, the Bulgarian Minister of Internal Affairs, outlining a nine month schedule of deportation for all the Jews of Bulgaria.

The Dannecker-Belev agreement would be carried out in two stages with a contingency plan for second stage. The first phase of the plan involved the Jews living in Bulgaria’s new territories. The Jews of Thrace, Macedonia, and additional 6,000 “undesirable” Jews in Bulgaria proper would be transferred to deportation camps and lose their Bulgarian citizenship. Since the Jews in recently annexed Dobruja were considered ethnically Bulgarian, they were grouped with Bulgaria proper. The process was to begin in March and last approximately one month. The Jews were to be told they were being relocated within Bulgaria and not deported; a deceptive tactic similar to telling gas chamber victims they were going to the showers.

The second phase of the plan stated that all the Jews in Bulgaria proper, or “old Bulgaria,” were to be deported in a similar manner. Armed with the whereabouts of every Jew in Bulgaria, the KEV grouped them into ghettos. However, Warrant Number 127 stated that German authorities had the right to deport 20,000 Jews “inhabiting the recently liberated territories,” but made no mention of Bulgaria proper. This qualified choice of words might have unknowingly saved most of the Varsano families living in Sofia and the rest of Bulgaria proper.

The Varsano children were probably oblivious to the technicalities of the laws. The adults in the family, however, were aware and actively lobbied the Jewish political and economic groups to pressure the authorities while trying to ride the fine line of not being a partisan. They were just a regular law abiding family that wanted to work hard and have a peaceful life, not political radicals or violent protestors. The extent of their political involvement was isolated to issues of self preservation and they had no designs on ascension to power.

The loophole in the law bought the Bulgarian Varsano families some precious time which allowed more debate about Bulgaria’s policies on Jews. The totalitarian drive to legislate discrimination and genocide was a tricky legal maneuver, especially when years of human rights laws were already on the books. The rule of law still existed, corrupt as the system might have been.

More potential perils still lay ahead for the Bulgarian Varsano families though. It’s like a defendant getting acquitted because of a small point in the law rather than being found innocent by a jury of his peers. Lives might have been spared temporarily but they certainly did not return to their pre-war routine.

Many Jews tried to find loopholes in the legislation to save their own lives. Jews that married non-Jews were exempt from wearing stars and deportation. So a marriage of convenience became another tactic that could save a family’s doom. Certain Jews living in Bulgaria were exempt from many of the discriminatory laws because they held foreign citizenship. Many Sephardic Jews became Spanish citizens, some 450 years after their expulsion from Spain.

It was quite ironic that the descendants of exiles would want to go back to the land of the Inquisition but when you’re being persecuted, any place was better than where you were. The Varsano family probably would have gone to Africa, Australia, Antarctica, or any other safe continent. The history of the Jews was that of a nomadic people escaping persecution and migrating to whatever countries would accept them. Obviously, a safe place in Europe, Israel, or the US was the most preferable destination. Almost all Jews in Bulgaria still spoke Ladino and could assimilate into Spanish society easier than in other countries. Spain might have allowed a few Jewish political refugees on a case by case basis but the predominately Catholic country did not embrace mass Jewish immigration in the 1940s and the Varsano families remained stuck in Bulgaria.

Seeco and Seli Varsano got lucky in a way because they suffered from a contagious illness. While Isaac Varsano was on his work detail, the rest of the family received evacuation orders to leave Sofia and go a place called Razgrad. “Fortunately,” Seeco developed Peritonitis, an infection of the abdominal lining, and the health authorities restricted him to a quarantine area in their home. Seli became infected with the Mumps so the Bulgarian Red Cross put a warning on the front door that “Danger – Infectious Disease: No one allowed in, No one allowed out!” That ominous warning granted the family a temporary reprieve from being banished from their hometown.

It was yet another ironic moment of the times that a contagious illness was viewed as a positive development. They were able to spend a little more time in their home city but it only delayed their inevitable relocation. The opportune illness also illustrated to the Varsano family the sheer insanity of the antisemitic laws that being ill sometimes saved you from a worse fate. The ludicrous policies of the fascist government were sympathetic to ailing Jews but hateful towards healthy Jews. It seemed to me to be an unresolved moral dilemma of the authorities similar to someone who was on death row, but cannot be executed until they are deeming mental and physically well enough to face death. Rather than a death sentence, it was a forced relocation order to an unfamiliar locale with the possibility of eventual deportation.

Early in 1943, the KEV started implementing the deportation process. The KEV made a list of all Jews who were considered “rich, prominent, and generally well known,” and a collection of “subversive” Jews. The KEV top officials wanted to deport entire families over individuals, which made saving children from deportation very difficult. Excluded from these lists were Jews in mixed marriages, but the previously exempted Jewish war heroes were now condemned.

When word of the secret deportations spread through Bulgarian society, many people were outraged. Bulgarian Orthodox Christian leaders such as the Holy Synod and the Bishop of Plovdiv protested the deportations on moral grounds. The president of the Writer’s Union and other prominent labor organizations opposed the action for a variety of social and legal reasons. To find out the details of the deportation plan and how to counteract it, KEV officials were regularly bribed for information by Jews of the underground movement in Bulgaria.

The Jews of Sofia and Kuistendil were the most effective in mounting a protest to the government’s secret actions. Haim Rehamin Behar of Kuistendil learned about the exact wording of the decree that mentioned the deportation of the Jews of the “new territories,” but made no mention of the Jews of pre-1941 Bulgaria. Behar, a former classmate of Dimitri Peshev who was currently vice president of the Subranie, gave the influential political leader a strategy to save the Jews of Bulgaria.

In March of 1943, Gabrovski and Filov conferred and agreed not to deport any of the Jews in “old Bulgaria” at that time. Before the desist order could be conveyed through the proper channels, many Jewish families were rounded up for deportation, only to be released a few hours later.

The temporary reprieve by the government merely delayed an obvious policy of inevitable exile. Dimitri Peshev and forty-two members of the Subranie sent Prime Minister Filov a letter of protest regarding Bulgaria’s Jewish policy. A week later, a fierce debate broke out on the floor of the Subranie chambers. Since most of the forty-two members that signed the protest were in the opposition parties, the majority party voted to withdraw the protest. Consequently, Peshev was asked to resign his position as Vice President of the majority party, but initially refused. Two days later, a vote of no confidence in the majority ruling party failed and Peshev was forced to tender his resignation. Peshev’s protest as well as the not so public assistance of the other “righteous gentiles” showed my family that many fellow Bulgarians were willing to risk their own wellbeing to take a stand against the senselessness of the fascist state. The end result of Peshev’s courageous action was an opening of public debate on the previously covert process of deciding Jewish policy.

Two weeks before Peshev’s heroic protest occurred, deportations for the Jews of Thrace had begun. Every Jewish person living in Thrace was awakened in the middle of the night, evicted from their homes and told they were being transferred to the interior of Bulgaria. Most Jews knew that they would be sent to the extermination camps in Poland and claimed foreign citizenship as a last ditch attempt to survive. Jews in Thrace, who possessed foreign citizenship, including Bulgarians, were included in the initial round up but were later released and sent to forced labor crews in Southwestern Bulgaria.

The rest of the Jews of Thrace were placed in temporary camps awaiting deportation. The so called “departure centers” were mostly located in tobacco warehouses and empty schools which lacked sufficient supplies. The condemned Jews were sprayed with cold water and subjected to humiliating searches. The overcrowding and unsanitary conditions caused many illnesses. The lack of food, medication, and proper shelter in the camps resulted in several deaths per day.

Next, they boarded open railroad cars and endured a long journey where they received harsh treatments from mostly anti-Semitic guards. Some of the guards were just soldiers or police doing their job, they didn’t hate Jews but they couldn’t disobey orders either. A few of the guards treated the Jews as humanely as possible under the circumstances, but most were antisemitic and took sadistic pleasure in tormenting their Jewish detainees. They told the Jews that their destination had changed and that they were going to Palestine, but most knew this was a lie. On this cramped and freezing journey many fell ill and some died from hunger and exposure. While the Jews were imprisoned, their property was liquidated and the proceeds were put into the infamous frozen bank accounts or the Jewish Community Fund. Looting was common, perpetrated by every walk of life: policemen, judges, KEV officials, laborers, and other government employees.

In Pirot, a similar process was taking place but with even harsher implementation. Pirot was a small section of eastern Serbia forty miles northwest of Sofia that was transferred to Bulgaria in 1941. Jews of foreign citizenship, with the exception of Bulgarians, were not spared deportation. The guards were especially vicious at these deportation camps, where brutal beating of the men and raping of the women were widely reported. The awful journey by train mirrored what occurred in Thrace.

The Jews of Macedonia were the last group to be deported from the “newly liberated territories,” and were well aware of their impending fate. Some individuals managed to escape into Italian controlled Albania, but most were confined in the converted tobacco warehouse of Monopol Cigarettes, which was utilized as a concentration camp in Skopje.

The entire deportation operation required the conspiring of several countries of the Axis powers, but Bulgaria was the main player. The departure centers were under the authority of the Bulgarian State Railway and the KEV. From the regional camps, many Jews were transferred to Sofia which was the transportation hub of the nation and where many of the Jewish residents had already been relocated to a rural portion of the country. From the Bulgarian capital city, they would be moved to the border town of Lom. In Lom, some railway cars would wait for days with the overcrowded Jewish passengers screaming for help. From the port of Lom, the remaining Jews boarded ships up the Danube River on route to Vienna, Austria.

Once in the Reich, it was a fatalistic journey to Katowicz, Poland and eventually to Treblinka. The journey was supervised by German police but the security was done by Bulgarian officials. Meanwhile, my grandfather was busy laying rail road tracks and filled rail road beds with heavy gravel just a few miles east of where the deportations of Jews to Treblinka were routed. Whether he knew exactly what was going on at the time, we’ll never quite know. Truthful information was scarce which further elevated the family’s anxiety and uncertainty. Maybe their ignorance regarding factual accounts of the Bulgarian deportations spared them even more grief because they couldn’t have imagined how horrific the truth really was.

According to Bulgarian and German transportation figures the total deportations per country were as follows: 4,075 Thrace, 158 Pirot, and 7,160 Macedonia, for a total of 11,393. The liquidated funds from Jewish properties far exceeded the deportation costs, making it a profitable venture for Bulgarian government. All but twelve of the deported Jews perished in the gas chambers of Treblinka. The shame of these Bulgarian atrocities was an overlooked chapter of history. Read more and watch video of Jews being deported from Thrace.

From a list of Bitola deportees, Nissim Jakob Varsano was born in 1888 and worked as a salesman (also Kommissionar) in Bitola (Monastir), Yugoslavia (Macedonia). Virginia Varsano worked as a “Schneider” which translates to cutter or tailor. Varsano is listed as names whose origin is from Iberian towns according to the Bulgarian census in 1943 and surnames of the Jews of Monastir (Bitola). Nissim Varsano was sent to the Treblinka extermination camp. Both Nissim and Virginia are listed on the JewishGen Yizkor Book Necrology as perished in the extermination camps in 1943 following their deportation. According to Yad Vashem, “on March 11, 1943 the Jews of Monastir, together with the entire Jewish population of Macedonia (some 7,350 people in total), were taken by soldiers, police and Bulgarian officials to Skopje, the capital of Macedonia, where they were held at the local “Monopol” tobacco factory under deplorable conditions.

A few days later, on March 22, 1943, the first transport of Macedonian Jews was deported in sealed cattle cars bound for Poland. In the days that followed, on 25 and 29 March, additional transports departed, all for the same destination – Treblinka. From the 3,276 Jews of Monastir incarcerated at “Monopol,” all of them Yugoslav citizens, only five managed to escape. An additional three Jews were released by the Bulgarians. A number of Jews had fled before March 11 to Greece in the hope of being rescued, but almost all of them were murdered at Auschwitz. A few dozen young Jewish men and women from Monastir joined the partisans and fought in the different units; some of them were killed in battle, few survived.”

Bitush and Olga Varsano of Sofia had three daughters Roza Varsano, Rebeka “Beka” Varsano and Ester “Stela” Varsano and one son Isak. Bitush Isak Varsano was sent to the Samovit Concentration Camp. The rest of the family were interned to Vratsa. Read more about Roza Anzhel (nee Varsano) and her family’s WWII experiences.

When the Western powers started to learn about Nazi atrocities committed in Poland and elsewhere, world opinion began to affect the fate of the remaining Jews in Bulgaria proper. In March of 1943, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Secretary of State Cordell Hull, British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, and other prominent officials met in Washington to discuss the fate of the Jews of Bulgaria. Britain was now willing to accept 50,000 Jews into Palestine. Unfortunately, the US balked because they were unsure of the logistics and cautious against making a public statement. While America was tentative, millions of European Jews were perishing in the Nazi death camps and my family was desperately clinging to empty promises coupled with unsubstantiated rumors. A few weeks later, the Allies convinced neighboring Turkey to allow the Jews to stay there temporarily on their way to Palestine. This plan was never implemented because Romania and Bulgaria refused to provide the ships for transport, and the internal politics of Turkey broke down. A tepid effort by the American and British for emigration to Palestine never materialized for the hopeful and anxious Jews of Bulgaria.

By the spring of 1943, Bulgaria’s policy towards Jews had shifted from slowly carrying out the Nazi final solution to halting any new deportation plans until the outcome of the war was clear. The Axis powers were no longer favored to prevail. Boris was trying to hedge while he explored other strategic options. Anti-Bulgarian Partisans were increasing their military pressure within the Bulgaria homeland while Jewish partisans managed to assassinate a small number of right wing politicians.

In April of 1943, Tsar Boris traveled to Germany to meet with Adolph Hitler to discuss crucial issues regarding the war effort. Boris conveyed his feelings about the necessity of the Bulgarian Jews for road labor and that he only intended to deport the Jews of the new territories. The RSHA felt that Boris was making excuses and wanted all the Jews deported in quick order. The consummate compromiser, Boris agreed to deport 25,000 “communist elements,” while the rest of the Jews remained in camps and labor groups. That amount represented more than half of the surviving Jewish population in Bulgaria and the actual amount of communists among them was a tiny fraction.

While the country as a whole was moving away from antisemitic sentiment, KEV chief Belev was drafting new schemes for Jewish deportation. Plan A would immediately deport all Jews except foreign citizens, Jews married to non-Jews, persons the state needed, and those seriously ill. The actual process would mimic the deportation procedure in Thrace. Plan B stated that the Jews in the cities, including the Varsano families of Sofia, would be transferred to the interior provinces while awaiting deportation arrangements. Boris accepted Plan B, not Plan A, and it was eventually implemented.

On May 21, 1943 all the remaining Jews in Sofia received orders to leave the city within three days. The Bulgarian Orthodox Church and political opposition leaders staged public protests. Belev and Filov defiantly insisted that the Jews would be deported. In the Danube River port towns, empty steamships began to ominously cluster around the docks. The rumors of mass deportations had reached the forced labor camps, and somehow Isaac Varsano was able to go back to Sofia with the help of some of his Bulgarian friends to tend to his family. He made arrangements to transfer his wife and children to a small town near the Romanian border named Novi Pazar.

Urbanites Rachel, Mordecai and Sarah Varsano were going to be forcibly relocated to the countryside to live under primitive conditions amongst Turkish peasants. A daily routine in the fields was a drastic shock, but at least there was food and they were still in Bulgaria. The adult Varsanos secretly feared it was the first step to being deported and, in fact, if Belev and Dannecker’s original proposal was implemented, they would have eventually been deported as the latter half of the two phase process.

On May 24, a national holiday commemorating Saints Cyril and Methodius for their contributions to Bulgarian education, culture, and the Slavic script coincided with large scale public protest over Jewish policies. The leaders of the Churches and the Synagogues joined forces with Communist Party activists and stole the spotlight from the lavish parades. The police quickly responded by suppressing any large protest through incredibly violent means. The Varsano family remembers this day as a pogrom in Sofia. Gangs of Nazi-affiliated youth leagues roamed throughout the streets and brutally beat any Jew they encountered. Rachel Varsano spent that violent day visiting a friend and was still not home when the sun set. The entire family feared the worse, but a few hours later she returned and explained that she waited until the streets became quiet enough to proceed. The inhumanity of war time behavior made almost anything possible. Your mom could go out to visit a friend and be beaten to death by thugs on the street. Uncertainty, fear, distrust of neighbors, hatred of the government, and an overall feeling of helplessness made the honorable Bulgarians scared to stage any large scale public protest for fear of becoming a visible target.

Both the Jewish and Christian religious leaders devised a strategy to uphold the moral righteousness of Bulgaria. Metropolitan Stefan, after meeting with Rabbis Tsion and Hananel, sent a letter to Boris warning him “not to persecute the Jews lest he himself be persecuted,” and “God would judge him by his own acts.” Sympathetic church officials offered the Jews refuge and were willing to give them documents stating that they wanted to convert to Christianity. Belev responded to Stefan’s protests by claiming that the deportations were politically necessary and basically ignoring his pleas. Boris and Filov were continuing to hedge and began to reconsider the political necessity of deportations. Although internal pressures had some effect on Boris, the main determinant on deportations was the outcome of German military actions.

Plan B was going forward but some Jews were not going to go without a fight. Street demonstrations turned violent and the Bulgarian authorities cracked down with arrests and deportations to Bulgarian concentration camps. Apprehended Jewish partisans, members of the BKP, and other political prisoners were placed in the largest concentration camps where they endured the physical abuse of beatings and depravation, as well as the mental abuse of being threatened with deportation. At the Samovit and Pleven short term camps, the Jewish prisoners spent anxiety ridden days peering over the guarded fences at the empty ships on the Danube while they dreadfully pondered their impending fate.

Most Jews were sent to the interior provinces where they lived in crowded houses with other Jewish families or peasants. Men of working age, including Isaac Varsano, lived separate from their families with their assigned work detachment. The Varsano family went to Novi Pazar a few days after the May 24 riot. Novi Pazar was a small impoverished Turkish enclave left over from the Ottoman occupation. Jewish schoolchildren were not allowed to attend the local public schools, so every student received their instructions in only one humble room. They made the best of a bad situation with every bench in the classroom representing a different grade, Seeco was on the fourth and Seli was on the first bench. Even under these oppressive circumstances, Seeco still received some private lessons in English. Meanwhile in Sofia, Jewish property went up for auction, and an assortment of Bulgarians moved into Jewish homes.

Prior to the relocation order and the implementation of confiscation plans, the Varsano family tried to smuggle out as many heirlooms as possible. The only notable items that made it through the war were Isaac’s Swiss made chronograph watch with solid gold numbers and casing on a black leather band, a stainless steel Swiss Army style knife, and assorted family photos. The solid gold back plate of the watch was missing, however, which was most likely used as a bribe. The Varsano family tried to make arrangements for possessions to be safely stowed with their Christian neighbors, some successfully, some not.

Mordecai Varsano knew that his family had to hide some of their valuables, but didn’t realize the extent of the plundering. He naively hoped everything would, for the most part, remain the same when he returned home from his forced relocation. As a child, he was mostly confused about the entire episode of seemingly illogical events. As time passed and the restrictions became more severe, he became well aware of the reality of his persecution and his naivety turned into jaded resolve. Like any normal boy, he became attached to his neighborhood, as well as his few possessions, even more so than an adult. Nobody wants their toys taken away, especially all of them at once for no good reason.

The family was sent out to unfamiliar surroundings with barely any possessions. They could only imagine what was happening in their previous home as they tried to reestablish themselves in their new home. It was a nightmare that took many months to wake up from, but unfortunately, it was reality. They feared that burglars were breaking into their old home over and over again, and they were helpless to stop them. In fact, nobody needed to break in; they just moved in and legally appropriated the residence for themselves. While their fundamental rights of private ownership were being violated in Sofia, life on the fascist countryside was become more humiliating.

Little Seeco was arrested and beaten for not wearing his yellow star.

READ ABOUT MORDECAI VARSANO’S ARREST- Little Seeco Crosses the Bridge

Seeco Varsano survived the incident, but another Jewish girl from Sofia was not as fortunate. Sara Lurie was born in Sofia, Bulgaria in 1926. Her parents were Moshe Lurie and Regina Varsano. Seeco had a paternal aunt named Regina Varsano, but it is uncertain if this was the same person. Sara Lurie also had at least one sibling, a brother named Yom Tov Lurie who completed a Yad Vashem page of testimony about his sister.

For the early part of the war, the family remained on Positano Street in Sofia, but were forced to relocate to Shumen, Bulgaria. During this period of WWII, the Bulgarian Army, under the direction of the Nazis, operated a POW Camp in Shumen. In 1944 at the age of eighteen, Sara Lurie was beaten to death by the Germans because she gathered and spoke. Sara Lurie is considered to be one of the few Jews living in Bulgaria proper to have perished in the Shoah.

During the critical summer of 1943, German representatives again insisted on deportations. Boris and Filov continued to respond with the excuse of their imperative need for quality Jewish labor. The German ambassador to Bulgaria, Adolf Beckerle, tacitly accepted the excuse and recommended that Hitler should not continue to pressure Boris for deportations for fear of alienating the multicultural Bulgaria populace. Beckerle also recognized Germany’s military vulnerability and suggested waiting for a change in the war to resume deportation pressures. The RSHA and SS insisted on deportations from a military standpoint because they feared that the Jews were spies for the West and communist partisans. Beckerle concluded that Bulgaria desperately wanted to avoid being bombed by the Allied forces, and sculpted their Jewish policy and other foreign policies to achieve that goal.

The tumultuous summer also brought several rescue attempts for the Jewish people of Bulgaria. As the outcome of the war became more predictable and Bulgaria’s Jewish policy shifted, the government issued some Jews exit visas by the end of 1943. Many took unorthodox routes to Palestine in order to circumvent British authorities; a Jewish emigration technique used to great effect following the war.

As the summer progressed, the Axis powers had a major setback when the Allies invaded Sicily and Mussolini was forced to resign. Hitler now needed the Bulgarian forces to take over more of the military operations in the Balkans because Italy was ineffective. Boris and Hitler met to discuss a new defense strategy that involved the utilization of two Bulgarian army divisions to hold the front in Northern Greece and Albania. Boris wavered and only pledged one division. Boris knew the Germans could not stop the Russians and the West could not stop the spread of communism in the Balkans. After the Americans entered the war and the Germans were unsuccessful in conquering Russia, Boris prophesized that “[two nations] would inherit the estate- the Russians and the Americans.” With his vision of post war Europe in mind, he tried to position his country to minimize damage, no matter who won the war.

On August 23, after returning to Bulgaria from his meeting with Hitler, Boris retreated for some relaxation in the scenic Rila Mountains. After a hike on steep terrain, the forty-nine year old Tsar Boris III suffered a massive heart attack and died five days later. My family heard rumors that suggested that Bulgaria was ready to pull out of the war after the Italian collapse and that Filov’s government would be replaced by communists. Some people suggested that Hitler secretly poisoned Boris because of his reluctance to sacrifice all the Jews of his country and his refusal to send troops to the Soviet Union. Although, these conspiracy theories make compelling stories, the historical facts suggest that Boris simply died of an untimely cardiac arrest.

The successor to Boris was chosen by a corrupt Bulgarian fascist infrastructure under significant German influence. Filov and his friends in the German government, citing special powers during a time of war, bypassed the Bulgarian constitution and nominated Boris’ Brother Kiril as the chief successor, but Filov essentially still ran the country.

In October of 1943, Belev was asked to resign as head of the KEV when widespread corruption of the agency was revealed. Hristo Stomaniakov, an assistant prosecutor in the Sofia Appellate Court, replaced Belev and instituted a system based on a more objective legal adherence to the existing laws rather than a concerted effort to persecute Jews in any way possible. Many restrictions on Jews remained but did not worsen and deportations were out of the question. After years of deteriorating conditions for my family, the tide finally turned in favor of the surviving Jewish families of Bulgaria. In November of 1943, the Jews expelled from Sofia to the interior were allowed to return to their homes for ten days in order to “liquidate their movable property.”

As the Allied Forces victory became a foregone conclusion, the internal politics in Bulgaria became even more turbulent. The Red Army of the Soviet Union advanced deeper into Western Europe, emboldening the Bulgarian communist partisans to incite a civil war that did not succeed but added to the existing instability. The USSR questioned Bulgarian motives because of German ships stationed in Varna and threatened to declare war on them in order to secure them as a strategic partner. In November of 1943, American and British war planes bombed strategic targets in Bulgaria – mostly railroad stations and rail lines, possibly the same ones that my grandfather had spent months of forced labor constructing. In January of 1944, the Allies proceeded with mass aerial bombardment of Sofia and other crucial Bulgarian cities, rendering the Subranie building (seat of Parliamentary proceedings) useless. Large sections of major cities had to be evacuated while panic gripped almost every Bulgarian. My family had mixed emotions. There was a fear of being killed by a bomb, but there was also the anticipation of being liberated from the years of suffering under the fascist regime. Many Jews were hopeful that the bombings would force Bulgaria out of the Axis. My father and many others actually cheered the American bombers as they flew overhead.

After years of trying to ride the fence with the Reich and the Allies, numerous factors contributed to the Bulgarian government’s demise. The most dominant reason was the utter collapse and inevitable defeat of the Axis powers. Also the domestic policies of the fascist establishment had alienated and impoverished a majority of the Bulgarian population. Following Boris’ death, the rulers of Bulgaria were slowly losing their grip on power and increasingly vulnerable to internal opposition groups ranging from communists to pro-Western sympathizers. By the spring thaw, a new cabinet, headed by Ivan Bagrianov, was sworn in that leaned towards Germany and sought to prevent the spread of communism after the war. Bagrianov’s government also wanted to maintain the Saxe-Coburg dynasty and hold onto the annexed territories. To achieve these goals, the new administration would have to take a more moderate approach to the Allied nations. Some of the restrictions on Jews would be gradually lifted and the Bulgarians would not succumb to German pressure. The Soviets were also allowed to open a Consulate in Varna which represented a new chapter in the relationship. Life was slowly getting better for my family, but Bulgaria was still at war and the country’s political crisis was getting more convoluted.

In August of 1944, Bagrianov addressed the Subranie and requested that Bulgarian pull out of the war and their alliance with Germany. A few days later, the German Embassy in Bulgaria was closed and soldiers of the Reich were evacuated. Negotiations in Egypt proceeded to lay out how post-war Bulgaria would be structured. Bulgaria would not retain Macedonia or Thrace, but kept Southern Dobruja which it had acquired from Romania because the residents were considered ethnically Bulgarian. The Allies wanted to march through Bulgaria and to institute a new cabinet with no fascist or pro-German elements. On August 31, 1944 the cabinet abrogated all of the remaining restrictive legislation affecting Jews both in the ZZN and the decree law of August 26, 1942. Finally, Jews were allowed the same freedoms as all other Bulgarian citizens and the government promised to return all the confiscated property.

Consequently, Bagrianov’s government was replaced with a pro-Western administration led by the Agrarian Party’s Konstantin Muraviev and other former opposition leaders. This government was unstable at the outset due to all the conflicting agendas among the new cabinet members. The Soviets were also not pleased with the pro-Western government and pushed for the ascension of the Fatherland Front, a coalition of left wing political parties dominated by the communists. My family had absolutely no say in the formation of the government nor did their opinion regarding foreign policy matter to the non-democratic rulers. They had to band together with the other Jewish community and pray for a way out of the mess. On September 5, the USSR declared war on Bulgaria, finally causing Filov to resign his powerful position on the royal regents. Finally, one of the prayers of the Jewish community had been answered. To appease tremendous Soviet demands, Muraviev was forced to declare war on Germany. For a few ludicrous weeks, Bulgaria was officially at war with Germany, the Soviet Union, the United States, and Great Britain.

Four days after its declaration of war, the Red Army entered Bulgaria and the Fatherland Front seized control of key Bulgarian cities while arresting Muraviev’s cabinet. The Allies and the USSR officially recognized the new government led by Kimon Geogiev and agreed—in principal—to an armistice. On October 28, Bulgaria signed an armistice in Moscow that placed its armed forces at the disposal of the UN under the Soviet command. Even though the UN charter of a world organization wouldn’t be established until the following year, the United Nations that would administer post war Bulgaria was the Soviet part of a grand wartime alliance of powers allied against the Axis which was originally formed in 1941. Consequently, the USSR took control over industries, radio, transportation, and all other key components of Bulgaria society. The Bulgarians had to disband the Fascist Party and cooperate with the war crimes tribunal. Within a few weeks, the nation had been transformed from a fascist power in the Balkans to a satellite of the Soviet Union.

In November of 1944, the Varsano family finally returned to their home in Sofia. Unfortunately, their previous residence on Dragoman Boulevard was in the hands of wartime squatters, so they lived on Morava Street near the Jewish Quarter. Of course they were very bitter, but at that point they also felt a little lucky and just wanted to resume a normal life. The range of emotions was overwhelming: anger, resentment, frustration, relief, hope, vindictive, distrust, disappointment, as well as being anxious for a new start. The Varsano family developed a burning desire to get back to work and problem solve. There’s nothing that can’t be solved through hard work and perseverance, just block out discrimination and hatred as you go about your daily business. Everybody likes prosperity and a peaceful life, so striving towards that goal was an undisputed life ambition. The Varsano family still had to live in this country while they tried to look for safe way out to a better place.

At the conclusion of the war, the Jews of Europe received some retribution as war crime tribunals judged a slew of people deemed criminals against humanity. In Bulgaria, a war tribunal tried and executed various KEV members as well as former high level political leaders, including Filov, Mihov, Bagrianov, Prince Kiril, and many others. The guiltiest culprit of genocide was Belev who fled the country and was sentenced to death despite not being in custody.

Dimitri Peshev, who was defended by a Jewish attorney in recognition of his protest for the Jewish people, was spared a death sentence but convicted of crimes punishable by fifteen years of hard labor for collaborating with the Nazis by being a member of the wartime parliament. He was also accused of saving the Jews for money. Even a righteous gentile like Peshev was punished, despite the pleas of some in the Jewish community. He was released after being imprisoned just one year and died in 1973, impoverished and largely forgotten, in his hometown of Kyustendil in western Bulgaria. Peshev’s role in speaking up for the Jews only really came to light in the 1990s after the fall of communism. Before that the monarchy or the communists had been given full credit, depending on who was in power at the time. Recently, Bulgaria commemorated Tolerance Day on March 9 which corresponded to the day the Jews were spared from deportation. Unfortunately, it took over fifty years for Bulgaria to fully recognize the truth behind the events of WWII.

In the years following the war, there was an historical debate about “who saved the Jews of Bulgaria” The Jews of “old Bulgaria” survived the war in better shape than any other Jews in Europe, with the possible exception of Denmark. Had Boris and the Bulgarian people not tried to accommodate opposing factions, or if German military forces had been more successful in the summer of 1943, all of the Jews in Bulgaria would have been exterminated. So many Jews were exterminated within the Reich and so many soldiers died fighting, but the Jews of Bulgaria made it out of the war comparatively well. Complaining about almost being killed would have been considered an insult to all those who were actually killed, as well as those who survived the concentration camps within the Reich and emerged as mere shells of the human beings they once were. Suffering was a very subjective term to a Jew during WWII. Everyone suffered during the war; it was just a matter of how much. Life had to go on for the survivors. They simply picked up the pieces and moved forward. The prospect of death was not something they would dwell on, they were the survivors and there was much work to do in the coming years. They just tried to blocked it out of their minds and focused on the anything positive

Later generations of Bulgarians have promoted King Boris as the “Savior of the Jews,” but what about the slaughtered Jewish families within the new Bulgarian territories? What would have happened to all the Jews of Bulgaria if the Axis military forces had had a few more victories? What about the emotional and economic scars that the Jews suffered? For decades following the war, the survivors repressed their emotions and many eventual psychological ramifications would take years to properly diagnose. Many of the survivor’s emotions were repressed and it would take decades for the true stories to come to light. They tried to forget, but they simply could not.

THE USC SHOAH FOUNDATION INSTITUTE holds a video archive of the following members of the Varsano Family that survived the Bulgarian persecution of Jews and gave testimony in the Visual History Archive of Holocaust Oral Testimonies: