Greece: Greek Independence in 1832 to 1949 Departure

Greek Independence to Salonica becoming Greek (1832 to 1912)

Greece became an independent nation-state in 1832, but in Salonica where the bulk of the Varsano families lived, it would remain under Ottoman control for another 80 years. In 1896, the modern Olympics were revived in Athens but the very next year the Greco-Turkish War occurred. Known as “The Shame of ‘97,” the Greeks declared war on Ottoman Empire but lost to the Ottomans badly. The Greeks only win was autonomy for the Island of Crete.

As with much of world history, the Jews were blamed for the loss by the Christian Greek leaders. The Jews of Salonica, for the most part, were pro-Ottoman and disloyal to the Greek royalty. After many years of enjoying the relative tolerance of Moslem rulers and unmatched prosperity, they were suspect of the Nationalist Greek Christians. Jews in Greece in other parts of Greece, however, were more pro-Greek. Zionism in other parts of Greece would later became more popular than in Salonica where Ottoman rule was popular and the Jewish community was semi-autonomous.

Greek historian Rena Molho in her book The Jews of Salonica 1856-1919: A Unique Community writes that in 1897, Salonica is larger than Athens and has the largest Jewish population in the world in terms of the percentage of the populace. In Salonica from 1897-1923, Jews were a plurality of the population. The Sephardim controlled ports and important businesses. While Jews in other parts of Greece were a small minority and much poorer than Salonican Jews. Despite their initial pro-Greek leanings, those Jews were subject to more antisemitism.

The Jews of Salonica in the early 1900s thought it was inevitable that Greeks or Bulgarians would take over Salonica eventually. They were considered a Jewish Millet which was a legally protected religious minority. By 1900, the Jews of the Balkans had a relatively large population but no national ideology. Zionism in Salonica was considered more cultural than political and not an alternative to Ottomansim. HaMevasser (‘The Herald’) was a Zionist Hebrew-language weekly newspaper published from Constantinople from 1909-1911(Harbinger). It espoused many Jewish Nationalist Zionist theories. However, many elements of the Jewish Press were anti-Zionist. such as the Ladino publications El Tiempo and La Epoca, as well as the French publication Journal de Salonique. Ottomans still ruled Palestine at the time so they were staunchly anti-Zionist.

By 1911, the Greek ”liberation” of Macedonia was a more pressing concern than Zionism for Ottoman Jews who pledged loyalty to Ottoman authority. Since the 16th Century, the Jews regarded Salonica as a form of Zion, a promised land of refuge, the Jerusalem of the Balkans. The real Jerusalem was an underdeveloped Ottoman outpost with a limited Jewish presence and mostly populated by Muslim Arabs. For hundreds of years, Salonica provided a much better quality of life than Jerusalem for the Jews.

The younger Jews in Salonica aspired to the West and consequently started dressing and thinking differently than their parents. Formed in France in 1860, the Alliance Israelite Universelle provided education to in Salonica and other areas of the Balkans. These schools created a new generation of semi-secularized, Francophile youth. They mingled with non-Jewish neighbors. The cafes and theaters on Salonica’s shoreside promenade were teeming with the semi-Europeanized Jewish bourgeoisie. As they embraced modernity and new ideas, they turned away from old traditions.

By 1908, Zionism started to grow more popular in Salonica driven, in part, by these Alliance Israelite Universelle-educated young people. The Young Turk movement demanded reforms and the Jewish community became more vocal about fighting for self-determination. They started to be more combative with the antisemitic Greek Press. Only a few years after the first modern Olympics, the Jewish Maccabees Athletic Club was founded in December 1908. “Salonica is neither Greek, nor Bulgarian, nor Turkish; she is Jewish,” proclaimed David Florentin, a journalist and the vice president of the Maccabi club of Salonica, amidst the Balkan Wars (1912–1913). Strength and pride in the Jewish community were on the ascent in many aspects of life. However, unity and power would be needed because political change was coming that would be bad news for the Jews.

Eleutherios Venizelos was a Greek leader who led a revolt in Crete. His Liberal Party called Komma ton Filobrethem would go on to a 20 year rule in Greece. The party sought Greek unity with a major goal of the “liberation” of Macedonia. Part of this unity strategy was to protect Greeks outside of Greece, especially ones under Ottoman rule. They would actively attempt to Hellenize territories in Greece with a large minority population such as Jews.

In 1912, the 1st Balkan War resulted in Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia, and Montenegro surprisingly defeating the Ottomans. The Greeks took control of Salonica which Bulgarians had wanted. Bulgarian and Greek Orthodox Churches were rivals and the Greeks won this round of the rivalry. Greek Nationalism had triumphed as the Greek Orthodox Christians had essentially conquered the Ottoman Muslims. The Greek Christians were not only concerned with the Muslims though. From 1912 to 1918 the Greeks started eliminating Jewish autonomy and power that they had enjoyed under the Ottomans. In Salonica, the population was about half Sephardic Jews and the other half consisted of Orthodox Christians, Muslims, Donme (Jewish Muslim Converts), Armenians, Slavs, and Roma. The Greeks wanted homogeneity and Christian rule in the multicultural center of Salonica. In a city where old Spanish (Ladino), Greek, Turkish, Italian, Bulgarian, Serb, Romanian, and French were spoken among the multi-lingual populace, imposing Greek Nationalism seemed unnatural and oppressive.

In December 1912, the Salonica Jews wanted the internationalization of the city or Bulgarian rule or free Macedonia rule instead of Greek rule. Other Jews rejected the idea for fear of hurting Zionism. The Jewish community of Salonica was effectively split into two factions – assimilation and Zionism.

Greek Control of Salonica to WWII (1913-1939)

On August 10, 1913, in the Treaty of Bucharest Salonica officially became part of Greece. In Greek, the city is called Thessaloniki. The Greeks said they would have goodwill towards Jews despite the Jewish support of Turks. Germany, Spain, and Austria offered Jews citizenship and “protections.” Over the next 10 years, there would be more change in Salonica than the previous three centuries combined. The golden age of the Sephardim in Salonica would steadily erode. The Greeks wouldn’t hire Jews in the ports of Salonica, so Zionist Jews hired Salonican Jews to work the ports of Jaffa in Ottoman Syria (Palestine) and later British Palestine. The Jewish workers replaced the Arab stevedores (dockworkers). In time, the Jewish port of Tel Aviv started to eclipse the Arab port of Jaffa.

World War I to WWII

King Constantine I sided with Germany and Bulgaria during World War I. However, the political leader Venizelos was in favor of intervening and sided with the Allies during WWI. The Greek people were divided.

In the French newspaper La Liberté, on May 26 1916, it is written “In the week preceding the Israelite feast of Passover, one could read, in the French newspapers of Salonika, this notice “- to the officers and soldiers allies – The Chief Rabbi of Salonika has the honor to invite all the Israelite officers and soldiers of the Franco-English armies located in Macedonia to kindly attend the Seder service as well as the dinner which will be organized in their honor during the first two evenings and the first two days of Passover. The premises of the Chief Rabbinate were too small to contain all the guests, so the rooms of the Varsano Restaurant were rented for this purpose by the Israelite community, which will also be reserved for some of the guests.”

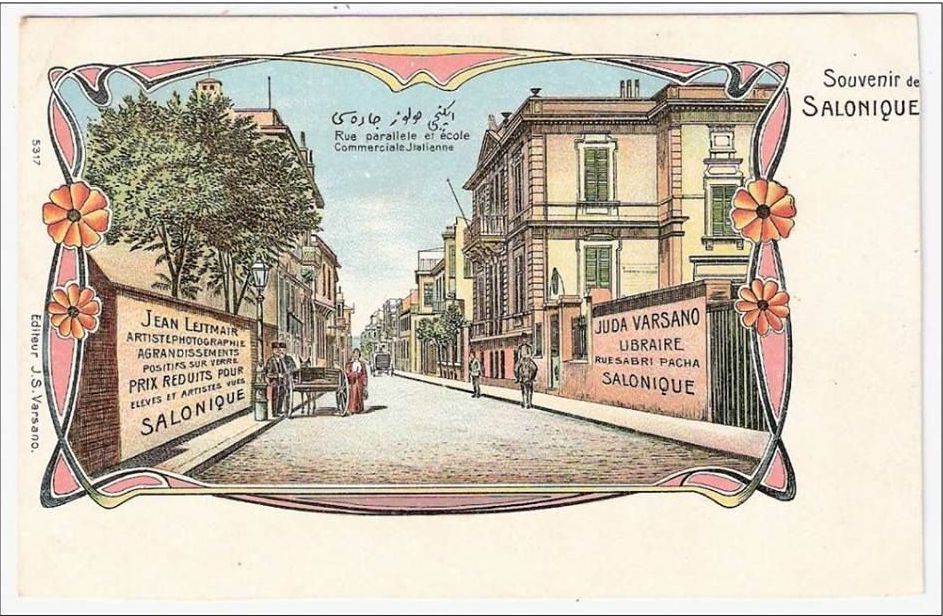

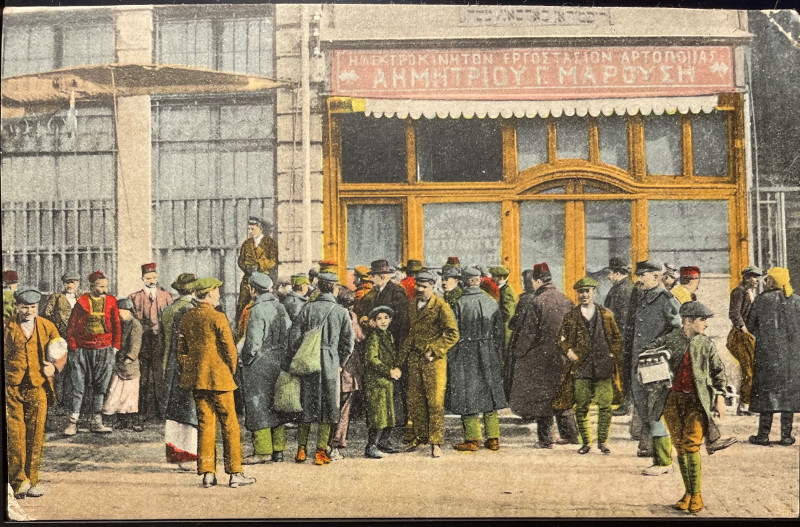

According to the University of Michigan blog post, the “Varsano Restaurant,” may be the same as the image depicted below. The photo is described as follows, “Newly added to the Jewish Salonica Postcard Collection, this card depicts a crowd of men in front of a narrow two-store building in Salonica (Thessaloniki), Greece, around 1917. The picture was taken by French photographer Henri Manuel (1874–1947), who served as the official photographer of the French government from 1914 to 1944. The building was located on Salonica’s Promenade and stood adjacent to the Jewish Nouveau Club — an organization established after 1908 by dissidents of another Jewish club, the Club des Intimes (founded originally in 1873 as the Cercle des Intimes, Salonica’s first modern Jewish club). The captions on the back of the card point out, in Italian, French, and English, that the building housed a bakery (and that no women were seen among the men standing in front of it!). Indeed, that bakery was the modern Electrically

Powered Bakery, located on the ground floor of the building — as indicated by the red and white sign, in Greek, above the entrance.

Above the sign in Greek, there is a Ladino (Jewish-Spanish) sign in Hebrew script with the words משה ארסאנו’ב ריסטוראן) Resṭoran Varsano Mosheh). That was the kosher restaurant Varsano and Mosse, located on the first floor of the building. The kosher restaurant and its Ladino sign testify not only to the ubiquitous presence of the Jewish community in Salonica at that time, but also to the imprint Sephardic Jews left on the linguistic landscape of the famous Balkan town. In fact, several historical postcards from Salonica depicted establishments that displayed Ladino signs.”

In time, the situation for Greek Jews did improve. Venizelos wanted Jewish support so he took a series of measures against antisemitic actions. Eventually, the Venizelos government gained the support of most of the Jewish community. To bolster this support, Greece was one of first countries countries to accept the Balfour Declaration establish a Jewish state in Palestine in 1917.

Great Fire of 1917 in Salonica

However, despite the optimism of the Balfour Declaration and ongoing Great War, an even greater tragedy would befall the Jews of Salonica and the Varsano families of Macedonia. Devin E. Naar in the Times of Israel’s article titled A Century Ago, Jewish Salonica burned – The home to the largest and most dynamic Ladino-speaking Sephardi Jewish community in the world was rebuilt, only to be destroyed anew

“On Aug. 18, 1917, a massive fire roared through the Mediterranean port city of Salonica, Greece, (or Thessaloniki as it is known today) then home to the largest and most dynamic Ladino-speaking Sephardi Jewish community in the world.

According to local legend, the fire erupted one Sabbath afternoon amid World War I when the coals of a war refugee roasting eggplants overturned. A fierce wind catapulted the flames into a major conflagration that left two-thirds of the city in ashes and 70,000 residents homeless, 52,000 of whom were Jews. Thirty-two synagogues, 10 rabbinical libraries, eight Jewish schools, the communal archives, and numerous Jewish philanthropies, businesses and clubs were destroyed.”

The Alliance Israelite Universelle burned to the ground. The heart and soul of the Jewish community in Salonica was ripped apart. Various groups and organizations tried to rebuild, but many were forced to live elsewhere. The majority of the displaced Jews, many of whom were educated at the Alliance, moved to Paris, France. The French migration started in 1921 and continued steadily continued while other Greek-ethnic groups displaced the Jews of Salonica.

After WWI, the Ottomans lost control over the land of Israel or “Eretz Yisrael,” and the British Mandate of Palestine took over control. By the 1930s, many Jews from Salonica immigrated to the land of Israel or “made aliyah,” mostly living in in Tel Aviv and Haifa. Tel Aviv had the largest community of Jews from Greece. Around 500 dockworkers and their families, mostly from Salonica, found employment and housing near the new port of Haifa.

Despite steady immigration over the next few years to France, Eretz Yisrael, the United States, and other countries, the majority of Jews remained in Salonica. They sought to rebuild their Jerusalem of the Balkans. In 1928, Ovadia Varsano was a small private Jewish School in Salonica with 32 students that was listed among a book with Jewish Schools available during the 1920s. Ovadia Varsano also matches the name of the Rabbi that wrote the books Chiddushei HaRitva from Amsterdam in 1729 and Chazon Ovadia from Salonica in 1775. Was the school named after the 18th Century Rabbi or did it have another connection?

The Varsano families not only ran schools, but were operating various business throughout Salonica during the first half of the 20th Century. The book entitled Jewish Entrepreneurship in Salonica, 1912-1940, An Ethnic Economy in Transition, by Orly C. Meron, lists the Varsano surname in connection with six different businesses:

- Cohen & Varsano – referred to as a Fashion Studio (Atelier de Moda) in Cartas lacradas: 1850 – 1917 by Dora Openheim

- Raphael Jakob Varsano & Co.

- Salvator J. Varsano

- Albert Varsano – possibly a private school

- Jacques Varsano – possibly the purchases and sales of canned meats

- Nahoum Fils Varsano

World War II and the Holocaust

During World War II, Greece was conquered by Nazi Germany and occupied by the Axis powers. 12,898 Greek Jews fought in the Greek army. After the Greeks surrendered, Germany, Italy, and Bulgaria divided the country into zones of occupation. The German troops and their Nazi ideology occupied large portions of Greece, including western Macedonia and the Varsano home of Salonica. The Germans had been gathering intelligence on Salonica’s Jewish community since 1937. Some 60,000-70,000 Greek Jews, or at least 81% of the country’s Jewish population, were murdered; especially in jurisdictions occupied by Nazi Germany and Bulgaria. Although the Germans deported a great number of Greek Jews, some were successfully hidden by their Greek neighbors.

At the time of the German occupation, around 43,000 Jews resided in Salonika. Most of the Jews of Salonica were deported and killed. On July 11, 1942, the Jews of Salonica were rounded up in preparation for slave labor. The community paid a fee of 2 billion drachmas for their freedom. In February 1943, the Germans concentrated the Jews of Salonika in two enclosed ghetto-like areas of the city. Between March 20 and August 19, German officials deported over 40,000 Jews from Salonika to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination center. At Birkenau, the SS murdered virtually all of the Salonika Jews upon arrival. Most of Salonica’s 60 synagogues and schools were destroyed, along with the old Jewish cemetery in the center of the city. Only 1,950 Jews of Salonica survived.

Below are the stories of a few Varsano family members:

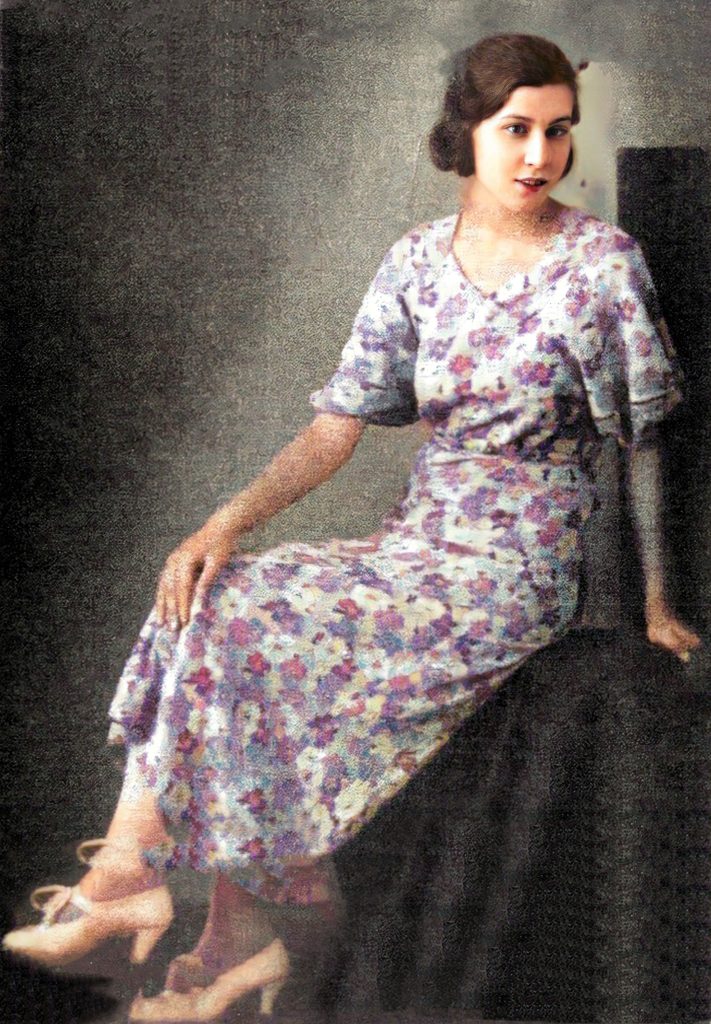

Bella Varsano was born in Salonica, Greece in 1913. Her parents were Yehuda “Juda” and Esther “Ester” Varsano. She lived in Salonica and worked as a school teacher. She was single. At the age of 30, she was murdered in the Shoah in 1943.

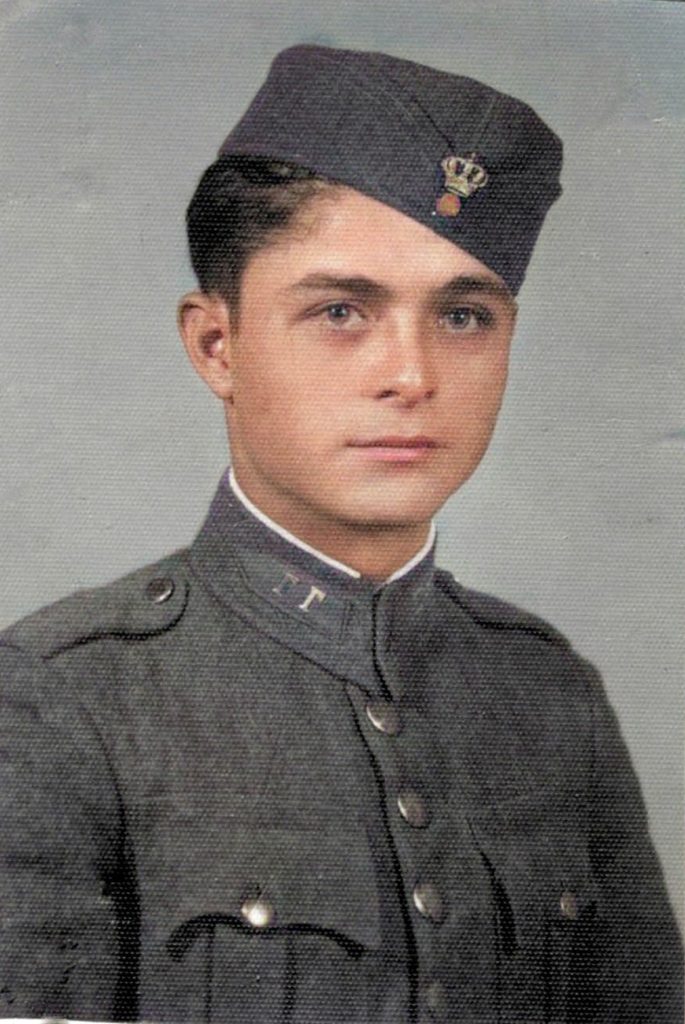

Daniel Varsano was born in Salonica, Turkey in 1908. His parents were Avraham and Ester Varsano. His parents perished in the Shoah but his sister Rakhel (Varsano) Shlomo managed to survive. Daniel was a soldier and served in the Greek military during the 1930s. He was single. At the age of 34, he was murdered at Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1942.

Yom Tov Izidor Varsano was born in Salonica, Greece in 1916. His parents were Yosef (born 1892) and Ester (born 1897) Varsano. He had a brother named Rafael Varsano (born 1919) and sisters named Jenna (born 1923), Simcha Alana (born 1927), and Rakhel (birthyear unknown). He worked as a clerk and served in the Greek military. In 1943, Yom Tov, Yosef, Ester, Rafael, Jenna, and Simcha were murdered at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Rakhel (Varsano) Elkaiam was the only member of the family to survive the Shoah.

Raful Varsano was born in Salonica, Greece in 1927. Raful gave personal testimony to Yad Vashem that gave details of his persecution and recovery during WWII. The 1989 testimony discusses his deportation to the “Baron Hirsch” Ghetto; deportation to Auschwitz; tattooing of a number on his arm; fate of his family members in camp; camp life including forced labor; death of his family members in camp; transfer to Mauthausen; transfer to Bergen-Belsen; liberation by the US Army in May 1945.

After liberation, he still suffered when he was moved to Athens by military aircraft; hospitalization; surgery on his spinal cord due to the beatings he received in camp; and had a nervous breakdown.

Salvator Varsano – letters from Sarina link, related to Jacques? and Esther the singer. Salvator Varsano was born in Salonica on March 17, 1907. His father was Juda Varsano and his mother was Lara (Aldnati) Varsano. His wife’s name was Uaino (Fadireni) Varsano and they had one child. Salvator was arrested for being a Jew on April 26, 1943 and arrived at Dachau concentration camp on August 8, 1944.

Peppo Varsano was born in 1911 in Salonica, Turkey. His parents were Samuel and Estria (Has or Alas) Varsano. His was Luisa (Lehaki) Varsano and they had one child. Peppo was arrested on April 2, 1943 for being Jewish, and arrived at Auschwitz on April 13, 1943. According to Yad Vashem, his fate was unknown.

Robert Varsano was born on October 7, 1929 in Salonica, Greece. His father was Samuel Varsano and his mother was Buena (Levy) Varsano. He confessed to being a Jew on April 21, 1942. He was arrested for being a Jew on on April 4, 1943 and was sent to Auschwitz, and then sent to Mauthausen on January 25, 1945. He was listed as a bricklayer. According to Yad Vashem, his fate was unknown.

Rabbi Albert Varsano was born in Salonica in the Macedonian area of the Ottoman Empire around 1883. He was married to Miriam (Perahia) Varsano and they had two children. Their daughter Donna Varsano was born around 1925 in Salonica, Greece, and was a student. Their son Mentech Varsano was born around 1927 in Salonica, Greece, and was a student. Rabbi Varsano worked as a teacher. In 1943, the entire family was murdered at Auschwitz-Birkenau in Krakow, Poland. Albert was 60 years old, Miriam was most likely in her 50s, Donna was 18, and Mentach was 16. All lost in the Shoah.

Greek Resistance During WWII

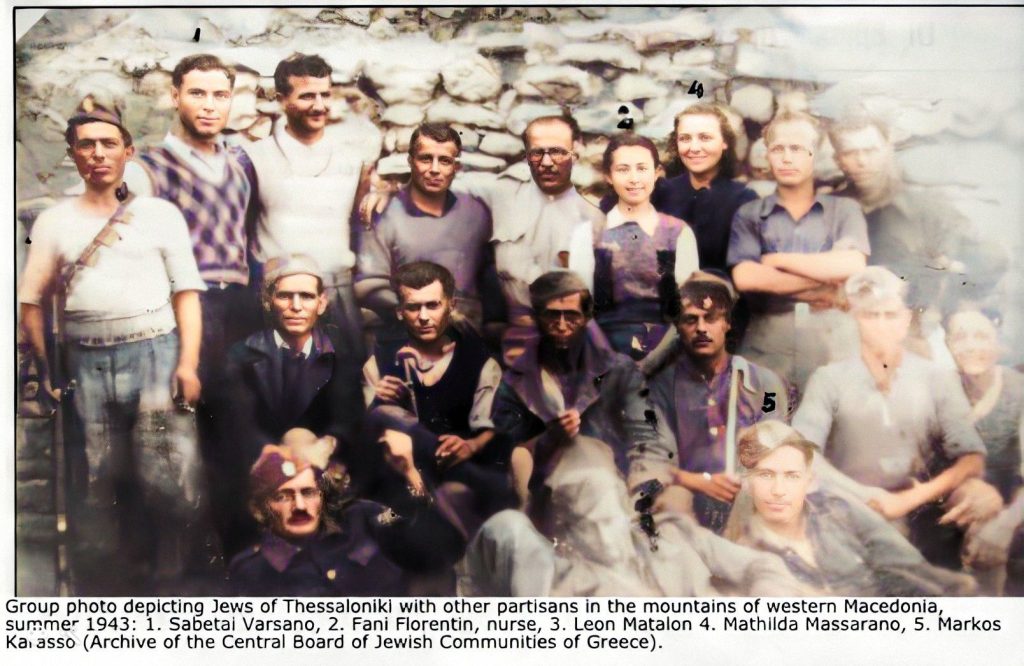

During WWII, Saby (Sampetai) Varsano was one of 876 Jews in the Greek resistance to the Nazi occupation.

The Few Survivors from Salonica during the Holocaust

Moises Varsano was born in Salonica, Greece in 1919 and worked as a waggoner. His parents were Shmuel and Perla Varsano (born in 1896), both of whom were murdered at Auschwitz in Birkenau, Poland. Moises, aka Moshe, was sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau which was both a labor camp and a center for the rapid murder of Jews by means of Zyklon B gas. Moises Varsano was also sent to Warszawa Camp, Kaufering Lager Iv Hurlach Camp in Germany, and finally to Dachau concentration camp. Moises, somehow, survived this horrendous experience and was liberated from Dachau on May 1, 1945 by the 42nd and 45th Infantry Divisions and the 20th Armored Division of the US Army.

Mordochai Varsano born on March 3, 1925 in Salonica, Greece. He was the son of Juda, who was a factory worker at Auschwitz and Rachel (Oro) Varsano. Juda may have went to Auschwitz in 1942. He worked as an electrician at Auschwitz. January 12, 1945 KL Auschwitz. Admitted to Auschwitz June 1945. Transfered from KL Buchenwald January 22, 1945. Imprisoned and deposited at Buchenwald January 22, 1945. Same as below? Son of Artist?

Mordekhai Varsano was born in Salonica, Greece in 1925 and worked as a print worker. His parents were Yehuda (Juda?) and Rachel Varsano. In 1943, Mordekhai was sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau and eventually to Dachau where he was liberated on April 11, 1945 accorded to Yad Vashem Survivor testimony.

Salvator Varsano was born in Salonica, Greece in 1907. His parents were Yehuda and Sara Varsano. His wife’s name was Ester “Eti” Varsano. Salvator survived Auschwitz-Birkenau, Dachau, Lager Buchberg, Landsberg, and Kaufering concentration camps in Germany, and was finally liberated from Freimann Traunstein (Oberbayern) in Bavaria, Germany.

The stories above are a mere sample of what the Varsano families of Greece experienced during WWII. Read more about complete list of Varsano families that were victims and survivors of the Greek Holocaust

Robi-Rafael Varsano was born in Salonica and survived the Shoah After WWII, detected Max Merten, military administration counselor of Nazi Germany in Thessaloniki.

Robi Rafel Varsano Z ”L– In Memoriam . One of the last survivors of the Shoah, the nonagenarian Robi recently died in his small homeland, Thessaloniki. We remember and honor the memory of this brave young man who, after suffering and hardship in the death camps, managed to rebuild his life. Indomitable like many of his coreligionists, full of strength and resilience, he raised a beautiful family and created an economic empire through his company dedicated to optics. We remember him through his fictionalized biography written by his son Sammy. Robi is survived by his wife and two children. Sauliko was the name of a tavern on the seafront in Thessaloniki. Every Sunday – Shabbat was no longer a Jewish holiday by law since 1924 – Robi Varsano frequented it until 1940, with family and friends. There he listened to the singer Sofia Bemba, one of his favorites. Freedom … ELEFTHERIA was the name of the Square where Robi saw all his family and friends registered one day in 1942 as carriers of an “old disease”. In the same square, in 1957, Robi accidentally recognized the “Diabolical Max” [Max Merten] who applied the “Final Solution” to all those who had the stigma of this “disease” in Thessaloniki. Robi called the police to arrest him, and they did. But Germany would not receive the Greek emigrants and would not make a loan of many millions if they did not set it free. Robi had thousands of stories to tell his fellow citizens about all those who were lost in Auschwitz. But Sauliko had disappeared along with her fans. Robi was left alone with the number 115365 that would never be erased from his left arm Left arm tattoo: 115365

The few surviving Jews of Salonica returned home to find their former homes occupied by Greek families. The Greek government did little to assist the surviving Jewish community with property restoration. Following the war, many Greek Jews emigrated to Israel. In August 1949, the Greek government announced that Jews of military age would be allowed to leave for Israel on condition that they renounced their Greek nationality, promise to never return, and take their families with them. The Greek Jews that moved to Israel established several villages, including Tsur Moshe, and many settled in the Florentine, Tel Aviv and the area around Jaffa Harbor. In Jaffa, the Greek Varsanos of Salonica would reunite with the Bulgarian Varsanos of Sofia.

The Righteous Ones: Yannopoulos, Ilias Yannopoulou, Popi (Recognized in 1971)

From Yad Vashem, “In Athens, Ilias Yannopoulos, a simple laborer, and his wife, Popi, offered refuge to the Matalon family, originally from Thessaloniki. Although there was no previous acquaintance between the two families, this did not change Ilias’s determination to offer a hiding place in his house to David Isac Matalon, his wife, Sol (née Revah), and their adult children, Isac David and Etty (Varsano). The Matalons, who had Italian citizenship, had resided in Thessaloniki until June 1943, when they were ordered by the German occupation command to move to Athens, then in the Italian zone. With the Italian capitulation, Italian citizens were no longer protected after September 1943, and the Germans included them in their persecution of all Jews in the capital.

On January 1, 1944, the Matalons’ refuge in an old-age home was discovered, and they urgently needed a safe place to hide. The woman who ran the old-age home and the priest of the institution began looking for a family who could accommodate the Matalons. Their efforts were successful when Yannopoulos entered the picture, demonstrating generosity and courage. The risks that the Yannopoulos family took were serious, because, in case of discovery by the Germans, they could have paid dearly–even with their lives. They constantly encouraged the Matalons, offering them moral support and hope for a better future. The hosts never showed regret or fear. Even though, once, the Gestapo discovered a Jewish family hiding opposite the Yannopoulos residence, they did not show any signs of concern; on the contrary, the hosts had to calm the Matalons. The friendship that developed during those months continued after the liberation. On May 25, 1971,Yad Vashem recognized Ilias and Popi Yannopoulou as Righteous Among the Nations.”