Ottoman Empire & Turkey 1492-1541 Arrival to Bulgarian Independence in 1878

Ottoman Empire 16th Century to Late 19th Century

Following their exile from Spain, the next destination for the various branches of the Varsano Family most likely included North Africa, Kingdom of Naples or other parts of Italy, as well as the welcoming Ottotman Empire. Some may have sailed directly from Spain around 1492 to the Ottoman territories, but most probably stayed in Italy for several years. After being forced out of Naples, every member of the Varsano Family eventually settled in the Ottoman Empire.

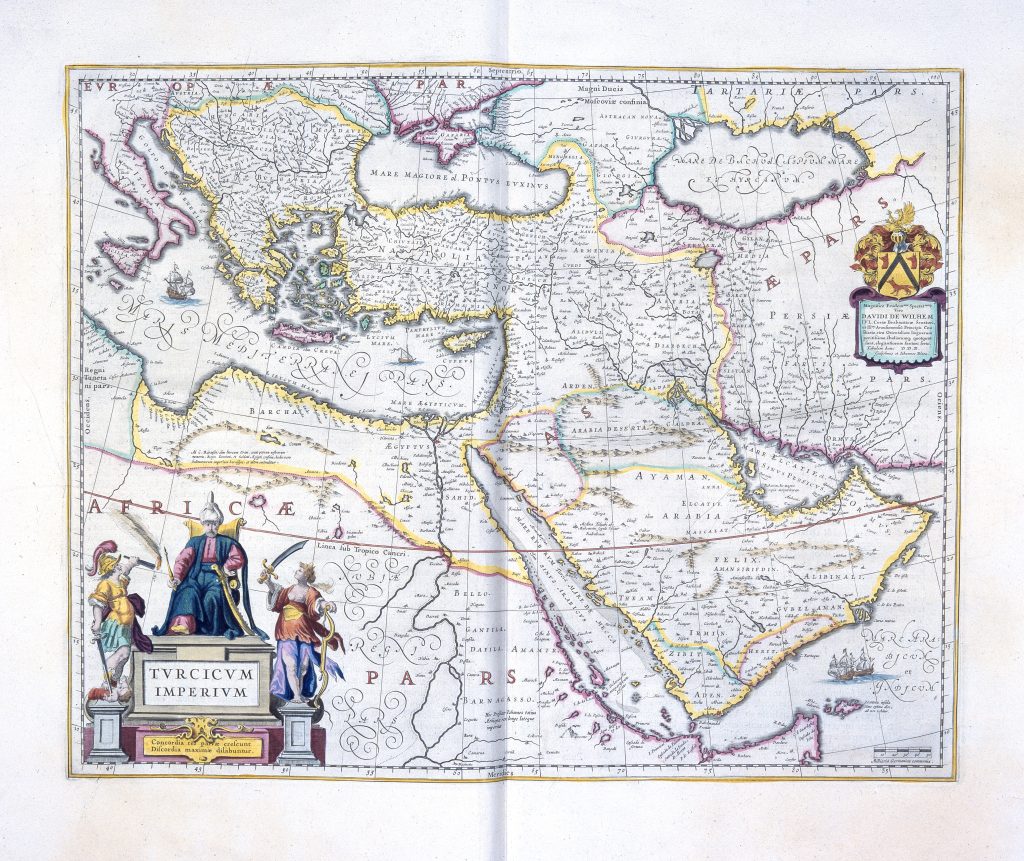

The Sultan Beyazit II extended the invitation of expelled Jews from Spain to Ottoman territories. Turkey, Greece, Bulgaria, Bosnia, Serbia, Albania, parts of Romania, Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, and Jerusalem were the new Ottoman home for Spanish Jewry. Most exiles were welcomed into pre-existing Jewish communities within the empire. The Turkish leadership of the empire had high esteem for the Jewish people. The Ottoman Muslims regarded the Jews as “people of the book,” part of the monotheistic tradition which led eventually to Islam. Moslems and Jews managed to live together in relative peace over next 400 years.

As the Sephardim settled along the welcoming Mediterranean communities, the extended Varsano family settled in several countries. Immigration records reveal citizens with the Varsano surname in Bulgaria and Greece. The ancestors of Jonathan Varsano, son of Mordecai, migrated inland to the non-Mediterranean and unfamiliar region of Bulgaria. The immigrants to Bulgaria came in four separate waves via Salonika, Constantinople, Adrianople, and Ragura. The third wave of Sephardic immigrants, including Varsano families of Bulgaria, settled in Sofia some time after 1497.

The Sephardic culture of the Spanish Jews mixed with Romaniot and Ashkenazi culture of the native Jews of the Balkan region. The rich tradition of the Spanish Jews quickly spread and Ladino became the predominant language of the Balkan Jews. The new Jewish community of the Ottoman Empire mostly lived in cities working as merchants and artisans, but also bankers and other financial services.

The Varsano families likely moved from the kingdom of Naples or other parts of the Italian peninsula to the Salonica area of the Ottoman Empire in the 16th Century. Many other Sephardic families living in the kingdom of Naples made a similar journey. Written records about the Varsano Family from the Ottoman Period are scant, but what exists shows the majority of the Varsanos lived in Salonica and some families later moved to the Bulgarian region of the empire.

In 1558, the Turkish-led Ottoman territories absorbed the bulk of Italian Jewish refugees. The Jews of Salonica gained political power and supported an economic boycott of the Italian port city of Ancona on the Adriatic coast. The Jewish merchants of Salonica, many from Italian families, were among the first Jews to organize economical for the benefit of greater community.

The great Sephardic culture had overcame adversity and thrived once again. The culinary tradition of the Spanish Jews now incorporated dishes from the heritage of Greek, Roman, Byzantine, Persian, Arab, and Ottoman culture. The flexible language of Ladino borrowed words from Greek, Turkish, French, Arabic and even some Bulgarian and Slavic additions.

There was a separate Jewish millet in the Ottoman system, through which Jews enjoyed some measure of self-government. A few politically adept Jews became influential advisors of the sultans. When the Turks completed their conquest of the Balkans in the 1500s, Sephardic Jews followed them into the interior, settling in the larger towns. In the area of Northern Greece, the city of Solonica became an Ottoman Center for Jewish life and the Jewish residents briefly held a majority in an area with a population of mostly Catholics.

Ottoman Greece

Despite the Ottoman Moslems relative tolerance of Jews compared to European Christians, the Ottoman legal system imposed restrictive rules on religious minorities: special tax (the jizya, the ispençe, the haraç, and the rav akçesi or “rabbi tax”), prohibition against carrying arms, prohibition against riding horses, prohibition against building new houses of worship or repairing old ones, prohibitions against public processions and worship, prohibition against proselytism, requirement to wear distinctive clothing, and prohibition against building homes higher than Muslim ones. Just like they had in Spain and other other lands of Diaspora, the Jewish minority group was able to thrive in a system stacked against them. According to Wikipedia, “During the Classical Ottoman period, the Jews, together with most other communities of the empire, enjoyed a certain level of prosperity. Compared with other Ottoman subjects, they were the predominant power in commerce and trade as well as diplomacy and other high offices. In the 16th century especially, the Jews rose to prominence under the millets.”

“The Jews satisfied various needs in the Ottoman Empire. The Muslim population of the Empire was largely uninterested in business enterprises and accordingly left commercial occupations to members of minority religions. Additionally, since the Ottoman Empire was engaged in a military conflict with the Christian nations at the time, Jews were trusted and regarded as potential allies, diplomats, and spies. There were also Jews that possessed special skills in a wide range of fields that the Ottomans took advantage of, including David and Samuel ibn Nahmias, who established a printing press in 1493. That was then a new technology and accelerated production of literature and documents, which was especially important for religious texts and bureaucratic documents. Other Jewish specialists employed by the empire included physicians and diplomats that emigrated from their homelands. In the city of Salonica, the heart of the Sephardic community, the Soncinos, a Jewish family from Italy established a press in the 1520s. (Borovaya, 2012) These early printers continued a tradition of informing and educating the community as well as being the genesis of a newspaper community in the Ottoman Empire.”

A collection of books from the 18th Century for sale in a Jerusalem auction that were printed in Livorno and Amsterdam with handwritten signatures and ownership inscriptions lists a Chiddushei HaRitva from Amsterdam in 1729. Handwritten signatures and ownership inscriptions with Sephardic script from various writers, the first of which is Ovadia Varsano. The sales copy also states that Ovadia Varsano is presumably the author of Chazon Ovadia from Salonika in 1775. The product description is the earliest reference with a specific date of a Varsano family member in Salonica. Various branches of the Varsano family tree surely lived in the Ottoman empire before the 18th Century, but many written records were destroyed or lost to time.

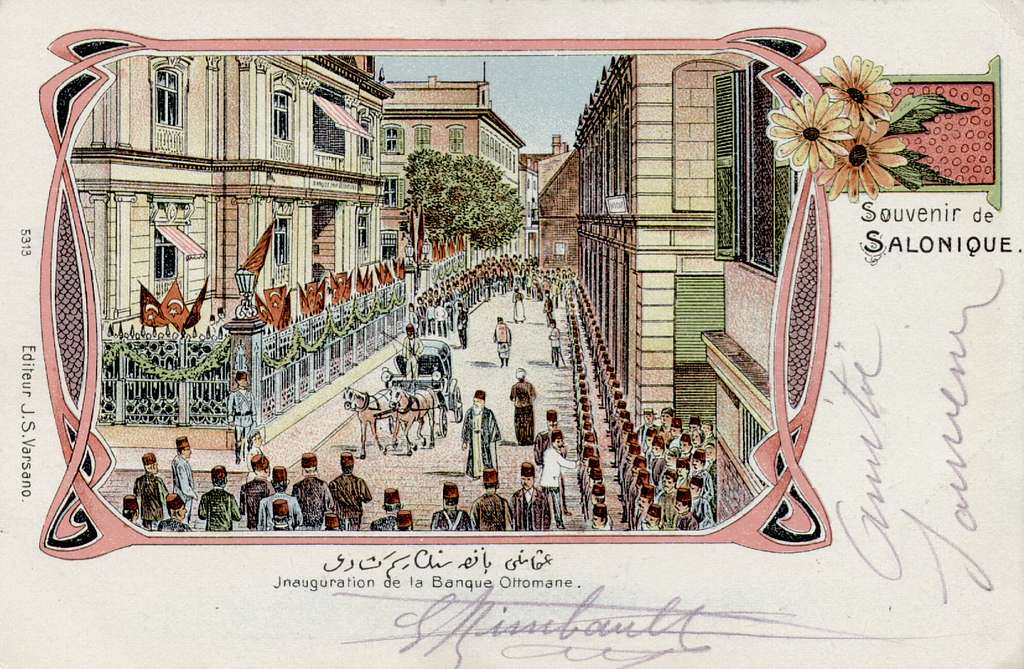

A few centuries later, Juda S. Varsano would carry on the important Jewish tradition using of the printing press in Salonica during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Along with photographer Jean Leitmair, they produced a series of postcards entitled “Souvenir de Salonique” which depicted various areas of Salonica during the early 1900s. Several of the postcards depicts Juda Varsano’s place of business, referred to as a bookstore but also appears to a publishing house, art studio, and seller of office supplies. The writing on the cards was mostly in French but also had some Turkish script. Juda Varsano most likely spoke several languages and catered to an international audience. Like most of Salonica’s Jewish population, Ladino was the most commonly spoken language.

Many Ladino newspapers and books were published by the Jewish community of Salonica. The language was not solely based in oral tradition, which allowed it to live on despite the persecution, death, and destruction that would occur just a few years later.

Salonica: Jerusalem of the Balkans

The Jewish population of Salonica. was 20,000 in 1553. Immigration was great enough that by 1519, the Jews represented 56% of the population and by 1613, 68%.

Wikipedia states “Although the Ottomans did not treat Jews differently from other minorities in the country, the policies seemed to align well with Jewish traditions, which allowed communities to flourish. The Jewish people were allowed to establish their own autonomous communities, which included their own schools and courts.The communities would prove to be centers of education and trade because of the large array of connections to other Jewish communities across the Mediterranean. In the sixteenth century, the leading financiers in Istanbul were Greeks and Jews. Many of the Jewish financiers were originally from Iberia and had fled during the period leading up to the expulsion of Jews from Spain. Many of these families brought great fortunes with them. The Jews of Salonica were well known for the spinning wool for the manufacture of broadcloth. The Jewish community thrived in various aspects of commerce and also had a relatively diverse collection of religious institutions.

In the “The Synagogues of Greece” by Elias Messinas, there is a description of both a Varsano Street and Varsano Synagogue in Salonica. Within the Salonica Jewish Quarter: “The Etz Hayim quarter was located in the streets Varsano (Pharoh), Etz Hayim Havrasi (Theodorou Laskareos), Hisar (Pausaniou) and the perpendicular street Kastilya Havrasi (Aghiou Nikolaou) that begins from the seashore and continues northwards.” The Varsano Synagogue of Salonica was founded by the Varsano Family during the Ottoman Period on Etz Hayim Havrasi Street in the Etz-Hayim quarter. “It probably stopped functioning before 1917.” There remains very little information about the Varsano Synagogue, but there is a tribute to the various synagogues lost in Salonica. According to Nahum Schnitzer writing in the Jerusalem Post “Their synagogues are memorialized on the walls of Yad L’Zikaron, the only active synagogue in Salonika. There, one can read the names of their original homes, such as Aragon, Portugal, Puglia, Castile, Lisbon and Italy.”

EDIT

The Jews who arrived from the Iberian Peninsula found there the old Romaniote synagogue Etz Haim and the more recent synagogues Askhenaz, Italia and Sicilia. Those who had originally come from Spain considered themselves more civilized and refined than the other immigrants and were inclined to remain aloof. They came from many areas and, like the Italian Jews, tended to group together by home town, city, or area of origin. Thus new Jewish communities became established and new synagogues were founded: Gerush Sefarad (Expelled from Spain), Castilia, Catalan, Aragon and Mayor(Majorca). Others were founded by Portuguese. Jews (Portugal, 1497 or 1525; Lisbon, 1510; Evora, 1512 or 1535) and by Jews from Calabria (Calabria, 1497) and Southern Italy (Puglia, 1502). The 1519 survey reports the 16 Jewish neighborhoods54 that recreated 15th-century Spain in Salonika.

The high intellectual level of the Sephardim resulted in cultural and economic revival. The city and its port acquired fresh life from the manufacturing activities initiated by the new arrivals. Of these activities weaving later became an established industry55 and soon of interest to the state. The Jews were especially skilled in wool spinning, an industry imported from Spain which spread to all localities around the Thermaic Gulf. Having once been granted the right to obtain raw materials at less than market prices and the exclusive rights to produce the fine woollen cloth used for garments worn by the Janissaries (1578), Salonika was soon swarming with telares (textile workshops); each terrace and each cortijos had its workshop: the whole city functioned like a huge spinning factory, dripping with water that gushed from under the door-sills and painted its streets in a variety of colours.

In the Salonika of the 16th century Jewish communities functioned like little “states” inside the city, diverse in language, rites, traditions and cultures, their respective synagogues expressing a tangible sign of autonomy. In this mosaic of cité synagogales56 the various Jewish congregations shared a self-determined body of laws covering religious and social issues (e.g. how new settlers were to be divided among existing congregations, how the Marranos were to be treated and how commercial activities were to be directed).57 Led by a Rabbi (a role which in many cases passed from father to son) and guided by the Assembly (attended only by those who paid community taxes), the synagogue acted as the soul of each group and formed the core of each neighborhood, the focal point in public celebrations and daily toil, business, haste. For immigrants it was a corner of “home.” To preserve the customs and rituals peculiar to their respective congregations, each synagogue had its own school, library and a seminary for higher studies, a philanthropic foundation and a burial society. The synagogue functioned as a center for administration of the law and the economy; butchers, bakeries and dairies were nearby, all supplying food in the way required by the Jewish religion.

When visiting Salonika in the mid-16th century, the French geographer Nicolas de Nicolay mentioned eighty synagogues,58 all of which had until then maintained their individual identities. Each synagogue was at one and the same time a religious and a civic structure, a historical and cultural landmark, a fundamental element of the “sentimental topography” shared by all members of

When visiting Salonika in the mid-16th century, the French geographer Nicolas de Nicolay mentioned eighty synagogues,58 all of which had until then maintained their individual identities. Each synagogue was at one and the same time a religious and a civic structure, a historical and cultural landmark, a fundamental element of the “sentimental topography” shared by all members of the community. When a synagogue was destroyed by fire it was rebuilt on the same sacred site.

From

In Search of Salonika’s Lost Synagogues. An Open Question Concerning Intangible Heritage

by Cristina Pallini and Annalisa Riccarda Scaccabarozzi

Transition to an Independent Greece

The basic history of Greek Independence from Wikipedia shows “The Greek War of Independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire occurred between 1821 and 1829. In 1826, the Greeks were assisted by the British Empire, France, and the Russia, while the Ottomans were aided by their North African vassals. In May 1832, Greece was formally recognized as an independent nation. The war led to the formation of modern Greece, which would be expanded to its modern size in later years.

The population of the new state numbered 800,000, representing less than one-third of the 2.5 million Greek inhabitants of the Ottoman Empire. During a great part of the next century, the Greek state sought the liberation of the “unredeemed” Greeks of the Ottoman Empire, in accordance with the Megali Idea, i.e., the goal of uniting all Greeks in one country.

In Constantinople and the rest of the Ottoman Empire where Greek banking and merchant presence had been dominant, Armenians mostly replaced Greeks in banking, and Jewish merchants gained importance.

The war would prove a seminal event in the history of the Ottoman Empire, despite the small size and the impoverishment of the new Greek state. For the first time, a Christian subject people had achieved independence from Ottoman rule and established a fully independent state, recognized by Europe. Whereas previously only large nations (such as the Prussians or Austrians) had been judged worthy of national self-determination by the great powers, the Greek revolt legitimized the concept of small nation-states, and emboldened nationalist movements among other subject peoples of the Ottoman Empire.

The newly established Greek state would pursue further expansion and, over the course of a century, parts of Macedonia, Crete, parts of Epirus, many Aegean Islands, the Ionian Islands and other Greek-speaking territories would unite with the new Greek state.

Ottoman Bulgaria

In 1396, the Islamic Turks known as the Ottomans conquered Bulgaria. The Jews were tolerated under the Moslem system while the Christian were discriminated against. The Turks showed little interest in forcing conversion to Islam, but many Christians did so voluntarily. Christianity did not have a long tradition in Bulgaria and the benefits of being Moslem were very enticing. The Jews, on other hand, had a long tradition of Judaism and were considered Jews before they were considered Bulgarians. The Jews were also considered a stateless people with no military defense which garnered sympathy from the Ottomans. Since the Bulgaria nation did not exist during the Ottoman period, the Balkan Jews within the empire were considered one people. In the 15th and 16th Centuries, the Jews of Bavaria were banished and immigrated to the tolerant Ottoman Empire. The result was a Judeo-German Askenazi community in Sofia.

Bulgaria had an even smaller Jewish population. Jews lived there since medieval times and were not treated badly : one of the tsars of the Second Bulgarian Empire in the 1300s married a Jewish woman. When Sephardic Jews came to the Balkans, the newcomers absorbed the older Bulgarian communities.

The Jews of Bulgaria had almost no need to even speak the dying Bulgarian language. Trade was conducted in Turkish, Greek, or Ladino. Jewish religion and scholarly pursuits were taught in Hebrew. The Bulgarian cities during this period were multi-ethnic but had a Turkish majority. By the 16th Century, the Ottoman Empire had reached its peak and the thriving Jewish community dubbed it “The Golden Age of Balkan Sephardim.”

However, it was short-lived and by the end of the century the so called Golden Age was receding. After years of Ottoman taxation and a repression of Bulgarian culture, economic stagnation and external pressure started to decline the power of the empire. Militant Christian sects from the imperialist nations to the north began attacking the Moslem nations of the Ottoman Empire causing the displacement of many Jews. European foes from the North repeatedly attacked Bulgaria hitting the port cities of Nikopol and Vidin first. The Jews of these Danube River port towns were subject to the anti-Semitic persecution of the Northern European conquerors. Most of these Jews fled inland to the safety of cities like Sofia. By the end of the 16th Century, the Ottoman empire was a economic disaster and over taxation only worsened the problem. Scapegoating became more common and religious tolerance dwindled. The Jewish community suffered with the rest of the empire and became disillusioned. A false Jewish Messiah named Shabbetai Tsevi gave some of the faithful hope. Experiencing a similar spiritual despair as the Ashkenazim, the Sephardim turned to blind faith and false hope. In 1665, Shabeti Savee, a Turkish Jew, proclaimed himself the messiah. Many Jews drew inspiration and hope from this apparent messiah. He was charlatan! The Turks eventually arrested him and forced him to convert to Islam.

By the 18th Century, the Christian nations of Europe were growing stronger, while the Ottoman Empire was beginning to crumble. In Western Europe, many Jews became integrated into the greater society by being involved in commerce and government. Generally, they were elegant, wealthy, and accepted. The Enlightenment purportedly eased social repression and religious intolerance as well as scientific breakthroughs. The American Declaration of Independence of 1776 and the French Revolution of 1789 allowed religious freedom to spread to a wider area of the globe and provided even more opportunities for Jews.

Since Bulgaria was not a central part of the Ottoman Empire, the Jews in Bulgaria received a diluted form of the spiritual movements within the empire. The changes caused by the Reformation, Renaissance, and Enlightenment to the Christian community were barely felt in Bulgaria. The Bulgarians were always individualistic and lacked an enthusiasm for the trends of the rest of the empire. Bulgarians by their very nature are moderate people. Therefore, the Jews of Bulgaria did not really buy into the whole Messiah movement like the rest of the Balkan Jews. When the Messiah was finally revealed as a fraud, the Jewish community became disillusioned and religious teaching lost credibility. Traditional Jewish theological studies were replaced by cultural, social, and the political nationalism of the Zionist movement.

Jews were not active among Bulgarian nationalists in the 1800s because of their relatively favorable situation under Ottoman rule: there was fear that their position would worsen in a state that was Bulgarian in ethnicity and Orthodox in faith. In 1878, the Bulgarians and Russians defeated the ruling Turks of the debilitated Ottoman Empire, and an independent Bulgarian State was declared. The Ottoman Empire was completely unstable at this point which was not comforting to the Jews of the region. An environment of uncertainty and impending war caused many Ottoman Jews to flee with their Russian neighbors to the Americas. My family weathered the storm and stayed in Bulgaria for several more decades.

Every Jewish family has a nomadic story filled with oppression and triumph. The Varsano family finds its origins in France, Spain, Italy, Bulgaria, and Greece. Although generation after generation was subjected to the whims of history, my ancestors weave a unique quilt of experience over the years that explain who we are today. The traditions are a reflection of the past and an explanation of the present.